Virtual Environment and Lying: Perspective of Czech Adolescents and Young Adults

Štěpán Konečný

ABSTRACT

Keywords: lying, adolescents, emerging adulthood, virtual environment

Introduction

The history and development of the internet indicates that what draws people to the internet is not the enormous amount of easily-accessible information, but rather other people (Biocca, 2000). Thanks to an increasing level of internet penetration and computer literacy, the feeling of anonymity on the internet can lead people to believe that there is no outer control of his/her behavior. The environment of the internet is characterized by a lack of visual and auditory hints commonly used in face-to-face communication. So, the internet allows us to emphasize the parts of our personalities which we consider most important as well as to suppress those which we are ashamed of. We can present ourselves as rich, successful, humorous, younger or older (Döring, 2002). In accordance with Bargh, McKenna, and Fitzsimons (2002), the visual anonymity of the internet has a direct influence on the amount of self-disclosure and sincerity. The feeling of anonymity can lead users to behavior impeaching common social norms which would remain hidden in the real world (Reid, 1991).

The question of lying on the internet was not, in our opinion, described in proper detail with relation to the specific communication environment of the internet. We have thus decided to take these environments into account and also to try and emphasize the effect of age on various subjects of lies. We also consider the composition of samples problematic in previous studies, since they often were conducted on students and were not large enough. For this reason we have decided to carry out our research on a representative sample with a sufficient number of respondents, allowing the inclusion of not only gender but also other independent variables, such as the online environment (or forms of communication) and also various age groups. We focused on the 5 most frequent online environments in our study – email, chat, forums, instant messengers (IM-ICQ/MSN) and computer games. We excluded the environment of weblogs because lying there was already precisely described by Blinka and Smahel (2009). We also chose age as an independent variable for the variability of the importance of some subjects of lies in various age groups. In our study we focus on adolescents and young adults, whereas results are confronted with the age group of 27 and above, where a lesser level of computer knowledge can be expected as well as a lower frequency of internet communication use.

Our goal was to document the level of deception of others on the internet in the Czech Republic, where the internet penetration in 2006 was about 50% of users over 18 years of age (Galácz & Smahel, 2007). We especially focus on how lying in various environments of the internet differs, who is most often the recipient of lies and what are the most common motivations for lying.

How many people lie?

By lying, we usually mean misleading someone, both on a conscious as well as unconscious level (not in psychoanalytic terms). In the following paragraphs we will focus only on purposeful misleading of others. In 1992 lying on the internet was still considered rather uncommon (Curtis, 1992). After two years of observation of social interactions of more than 3500 players on MUD servers, which are used to meet people and play various roles in a fictive world, Curtis ends the study with a statement that suspicion of lying was most often expressed towards women playing woman characters. These were often aggressively requested to “prove” that they are not actually men in real life.

The share of lying in communication tends to differ in various studies. Cornwell and Lundgren (2001) made a comparison of “misleading” in virtual environments and real life. 22.5% (5% in real life) lies about their age, while 27.5% (12.5% in real life) lied about their physical appearance. 15% (20%) lied about their hobbies and 17.5% (10%) about their job and, education. The relatively large age spread of 18-55 (with an average of 26) could however be considered a certain drawback of the study.

Caspi and Gorsky (2006) focused on participants of discussion forums, where 68% of respondents were women with an average age of 30. They found that whilst online lies were considered a widespread phenomenon (73% of respondents thought so), only one third admits to lying to others. They also found that people who spend more time online lie more often, and the same can be said about younger users (36% of users younger than 20 lie, while only 15.9% older than 31 do) and more experienced users. Respondents most often mentioned “playing a different identity” as the reason for lying, followed by fear of misuse of personal information. Whitty (2002) analyzed 320 chat users with an age average of 21.3. Through a questionnaire of her own making, she monitored the differences between the age groups of 17-20 and 21-55 as well as between men and women for lying about age, gender, work, education and income. She found that, except for lying about age, men lie more often than women and that younger age groups lie more often about age and education. Based on these studies we can conclude that younger respondents will lie more often than older ones (hypothesis H1).

Context of lying

The potential for experimenting with various types of characters is almost unlimited in online communication (Rheingold, 1993; Reid, 1991; Turkle; 1995; Suler, 2000 etc.), gender-swapping isn’t uncommon either (Lea & Spears, 1995; Wallace, 1999; Reid, 1995). However, there can be many other reasons for lying to other users. Up to 80% of lies are made for better self-presentation of ourselves (Kashy & DePaulo, 1996). We want to look better, smarter, more capable, make a better impression than we believe our true character is capable of (Whitty, 2008). We can thus expect that women will lie more often to men, and vice versa (hypothesis H2). In this context we also expect men to lie more often about their employment, education and income – to increase their appeal to the opposite gender (hypothesis H3), while women will more often “alter” their age and appearance (H4). We did not investigate the sexual orientation of respondents, these hypotheses however assume the majority of respondents to be heterosexual. Rowatt, Cunningham, and Druen (1999) describe the motivation to be compatible with wishes and expectations of other people, to avoid disappointment. Joinson and Dietz-Uhler (2002) consider the possibility of psychiatric diseases which manifest on the internet as attention-seeking by deceiving others or e.g. in the form of simulating an illness (or a problem) and then enjoying the help of various support groups.

Another possible reason for (not)lying could be the wish to express one’s true self. The internet could be considered a virtual laboratory for the discovery and experimentation with various versions of self in relative safety. Higgins (1987) distinguishes between the ideal, the ought and the actual self-concepts. The ideal self contains those qualities which an individual is trying to attain, the ought self those which he should attain and the actual self those which he currently has. Bargh, McKenna and Fitzsimons (2002) in their research not only expand on Higgins’ theory, but also on Carl Rogers and his concept of one’s true self which includes some unexpressed qualities and characteristics, usually not represented in front of others. The authors believe that internet communication allows one to better express one’s true self. An individual’s true self is more active during internet communication than when communicating face to face. Based on Bargh et al. (2002), we feel a real need for being seen by others in the same way we see ourselves, which is also supported by findings of Siibak (2009). However, some people find it hard to express their true self in the social environment in the real world, which could result in social anxiety. Interaction through the internet can thus serve as a form of protection or manner for temporary reduction of this anxiety. Amichai-Hamburger, Wainapel, and Fox (2002) support the results of Bargh et al. and prove that it is mostly introverts who have a greater tendency for situating their true self online. At the same time, people who consider it easier to express their true self on the internet than in real life are more open to creating close relationships with people they meet online (McKenna, Green & Gleason, 2002).

Whitty and Gavin (2001) also considered lying about one’s identity for security reasons, typical especially for women. Women can thus more explicitly express sexual desires, without fear of negative consequences (forced sex, pregnancy).

Tyler and Feldman (2004) as well as DePaulo and Kashy (1998) noticed the importance of the actual recipient of lies. It is easier and more common to lie to individuals to whom we have no emotional link and who we are not familiar with. On the other hand, it is harder to lie to those we consider close to us, or who are members of a certain community (be it real or virtual) where we have been meeting them for some time.

Particularities of virtual environments and possibilites of lying

The research of lies on internet servers cannot be carried out without first looking at the specifics of individual virtual environments in which people are most often found. Each of them can then influence the user with their character to act a certain way. If the environment is interpreted as highly unreliable, the user does not have many reasons to act differently either. This representation is, in our opinion, one of the possible factors influencing behavior in such environments. For some internet groups, the norms could be apparent and unambiguous. An important role is played by the consistency of a group as well as the frequency of meetings. If the group has existed for some time and the members of the group do not change too often, norms are “clearer”. On the other hand, groups meeting ad hoc or short-term groups and collectives generally have less clear norms (Reicher, 1987). These groups are quite frequent on the internet; open communities are common on the internet. We come in contact with such open communities commonly on the internet, much more often than with closed groups.

The most typical and also oldest representative of internet communication is the well-known email. It is common to have more than one e-mail address, whereas the difference lies usually in the amount of information these addresses provide about their owners. As Utz (2004) points out, people intentionally distinguish which email address to use for specific situations. Various email addresses can also be used for experimentation with one’s identity, especially during adolescence.

Chat rooms are unambiguously the least reliable source of information about the user. The created accounts do not usually serve a long-term purpose, and so they are frequently used for experimentation with identities. This is also related to the expectation of users about the reliability of provided data, which are not usually very high. However, Rollman, Krug, and Parente (2000) claim that gender had no influence on the communication in chat rooms – their results originate from monitoring the reaction speed of males to messages from females and from the absence of common courtesies between men and women. The authors explain these results by the near-impossibility of verifying the actual gender of other users. We can thus expect chats to be the least reliant source of information of all our environments (H5).

Discussion forums typically focus on a certain specified area of problems or subjects. They can focus on the resolution of certain types of problems, hobbies etc. Here, similarly to the situation on “self-presentation servers”, users most often represent themselves, especially if they wish to remain active on the server for a longer period of time. Reputation systems are not uncommon either – if the user helps someone, he will receive positive feedback on his profile, leading to a gradual increase in respect. This also forces users to behave in accordance with proper social conventions. Motives often include the wish to be admired and respected by others (Ekman, 1997; DePaulo, Kirkendol, Kashy, Wyer, & Epstein, 1996). In contrast to chats, discussion forums can thus be expected to be relatively reliable (H6).

The environment of computer games is special by its often competitive character and by the relatively large representation of men in this environment - Griffiths, Davies, and Chappell. (2004) claim that up to 81% of players are men. According to Blinka (2008), 96% women play a character of the female sex, but only 77% men play a character of the male sex. Since online computer games can be considered typically masculine, we can expect this to effect behavior to women – playthings. Women or girls are relatively rare in such environments, and thus can receive special attention and benefits. We presume that boys will lie more often than girls in playing computer games (H7).

Instant messengers (e.g. ICQ, MSN) form a very popular form of synchronous communication. This manner of communication has a more private character than the other environments. Communication most often occurs between people who already know each in real life – friends, family, peers. Instant messaging can be used as another level of communication e.g. after meeting someone in the other community environments. Norms are not explicitly listed here, however thanks to a limited feeling of anonymity and the possibility of recording communication (Jeffrey, Jennifer, & Thompson, 2004), we can expect a relatively stable environment with a low frequency of lies. We expect IM to be one of the more reliable means of communication, contrary to chats (H8).

The various aforementioned motives usually do not strictly occur only in the individual types of listed environments – such motives can blend together.

Method and research sample

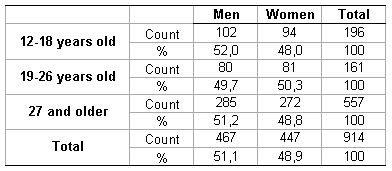

The presented research was realized by the survey, which is part of the wider framework of the World Internet Project: Czech Republic 2007. Data of the survey was collected by face-to-face structured interviews. The respondents were asked to select the appropriate answer for our created questions related to the respondents' lying online. The original selection sample included 1692 individuals of 12 and older, and is representative for the Czech Republic by the criteria of gender, education, age, region and domicile of the respondent. Of this sample, we have selected those who have answered positively to the question “Do you personally use the internet, meaning web sites, e-mail or any other part of the internet at home or any other location?” The results were elaborated for 914 users of the Czech internet, which form 54% of the original sample. Of these respondents, we have selected for in-depth analyses those who positively answered to the question: “Sometimes people lie on the internet. Have you told anyone a lie on the internet in the last 6 months?” We have also asked the respondents: “Who have you most often lied to? To a man, woman, or everyone in the appropriate environment?” For measuring the level of occurrence of various subjects of lies, we have asked about lying in each of the various communication environments separately. The environments were: e-mail, chat, discussion forums, IM, computer games. The list of chosen subjects included: age, gender, work, education, income, physical appearance. The results were compared for men and women as well as for the age groups of adolescence (12-18), emerging adulthood (19-26) and adulthood (27 and older). The number of men and women in individual age categories is listed in Table 1.

Results

Lying

In this chapter, we describe the frequency of lying on the internet in the Czech population, emphasizing the differences between men and women and between various age groups. We are aware that several other studies on a similar subject were already carried out (Whitty Gavin 2001; Whitty 2002; Caspi & Gorsky 2006), however we have included this part due to some ambiguous results in these studies.

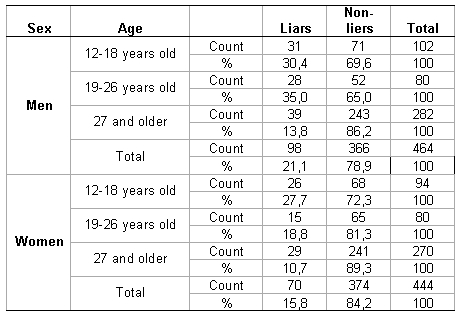

Our results indicate that approximately 18% of internet users list untrue information about themselves, of that 21% are men and 15.8% are women, χ2 (d.f.= 1) = 4,122; p < 0,05. Relatively large differences can be seen in various age groups, see table 2, χ2 (d.f.= 2) = 36,152; p < 0,001. About one third of users below 26 years of age admit lying on the internet, whereas the ratio is much lower for adults (12.3%) and notable differences can be seen between the groups of adolescents and adults, χ2 (d.f.= 1) = 29,193; p < 0,001, as well as the groups of young adults and users aged 27 and over, χ2 (d.f.= 1) = 20,596; p < 0,001. Hypothesis H1 – that younger users would lie more often than older ones – has thus been confirmed. Men aged 19-26 years are an exception, since they lied more often than boys ages 12-18.

If we look at the structure by gender (Table 2), differences persist for men, χ2 (d.f.= 2) = 23,511; p < 0,001, as well as women, χ2 (d.f.= 2) = 15,735; p < 0,001. In accordance with the previous model, a higher frequency of lying can be seen for men between 12 and 26 (although the frequency still slightly grows in the period of “emerging adulthood”), and the typical decline after 27 years of age. For women, the situation is different – there is an almost linear decrease in frequency of lies with age. The difference thus manifests especially in the middle group (in other words, while men keep their frequency of lies up until they become adults, we see a gradual reduction of the frequency of lies for women).

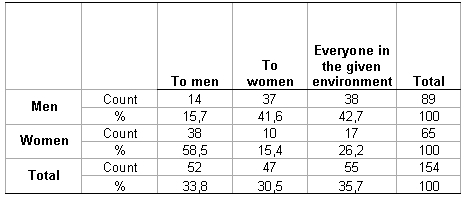

Recipient of lies

It is noticeable that men lie most often to women, or eventually that their lie has a “global character”, or in other words is not addressed to any individual but rather everyone present in a given environment (Table 3). Women admit lying to individuals of the opposite gender in a similar frequency, however they do not tend to make “global lies” as often and have approximately only half the frequency of men in this respect, χ2 (d.f.= 2) = 31,634; p < 0,001. This trend can be seen in every age group in our study. Hypothesis H2 has also been confirmed. Lying to the other gender is many times more frequent than lying to the same gender.

Subjects of lies and the internet environment

We have focused on comparing various age groups in our study; this might help better understand possible developmental stages typical for each such stage. When comparing general frequencies of lying between men and women on various subjects, we have found no significant differences, except for the case of men lying more often than women about their income, χ2 (d.f.= 1) = 6,009; p < 0,05. However, due to the number of respondents we do not consider this slight difference too significant.

Table 4 summarizes the basic differences between individual age groups for each subject of lies. The highest rate of lying about one’s age is found in the group of youngest women. In the age group of 12-27, the rate of lying radically surpasses the rate of lying of adults. An exception would be the group of women aged 19-26, where no differences were found, respectively were not significant, χ2 (d.f.= 1) = 5,809; p = 0,016.

Our second monitored subject of lying was one’s gender (so-called gender-swapping). This phenomenon was so rare in our study that the following results are only listed for illustrative purposes. Men (χ2 (d.f.= 1) = 46,129; p < 0,001) and women (χ2 (d.f.= 1) = 7,040; p < 0,01) aged 12-18 both lied about their gender more often than adults (27 and over). While emerging adult men (19-26) lied more often about their gender than adult men, χ2 (d.f.= 1) = 24,031; p < 0,001, we did not see a similar effect for women.

In comparison with the group of adults, lying about one’s work or school is much more typical for men and women in the age group of 12 to 26. The highest representation can be seen in the group of men aged 19-26. Education is often the subject of lies for men in the same age category, for women we found no differences in this respect though. The same group of men aged 19-26 is also the most frequent liar with regards to income.

Lying about one’s appearance is notable for adolescents and young adults; both these age groups lie many times more often than adults.

Hypothesis H3 – that men would lie more often about their employment, education and income – has been partially confirmed. It seems the hypothesis holds for education and income, but not for employment. The increased frequency in lies was only present in the age group of 19-26 however. Hypothesis H4 – that women would lie more often about their age and appearance than men – has not been confirmed.

We have also compared the frequency of lying in various forms of communication on the internet, in various age groups and with respect to the respondent’s gender and the subject of lies (Table 5). The numbers in the table list the percents of positive answers listed in each of the subjects. We select only the most frequently listed subjects of lies from our results, for age categories as well as for the respondent’s gender. We denote the percents representing the highest rate of lying of all internet environments. We do not list significance in individual groups due to the low expected frequencies in some groups, the results are thus only illustrative. The highlighted percents will help our orientation in individual environments on the internet, where the followed subjects of lies most often occur. It is clear that, in total, the least lies can be found in email communication. The highest frequency of lies is to be found in chats, hypothesis H5 has thus been confirmed. Lying through IM and on internet forums is much more frequent than expected, and so we must reject hypothesis H6, however hypothesis H8 has been confirmed even despite the higher frequency of lies on IM. In these two environments one must also take into account the age of lying users, which in most cases did not exceed 26 years. Lying in computer games is relatively rare, and similarly to emails is most often practiced by men, hypothesis H7 thus holds. The environment of computer games is also the only place where men lied about their gender much more often than women.

If we then give a closer look to the individual types of lies and age groups, we find that in chat rooms women and men aged 12-18 most often provide untrue information about their age (31-34 %). Chat rooms are also visited by emerging adult men, who lie about their age in up to 28% of cases, and also about their education, income and appearance in 14-17 % of cases. Women in this age often alter their physical appearance (31 %), as well as their age (27 %) and job (15 %). Similarly, women aged 19-26 lie about their age, education and appearance through IM. The frequency of lying of men and women aged over 27 usually does not exceed 7 % of cases in various internet environments. For this age group, the most frequent type of lies would be lying about their age on chat rooms (15-24 %).

Discussion

In our study, 18% of all respondents admit that during the last 6 months they lied to others in the environment of the internet. On the other hand, another study (Caspi & Gorsky 2006) lists lying in up to 29% of all respondents. If you consider in more detail the age differences in the research sample, the study of these Israeli authors notes that age increase correlated with a reduction of the frequency of lying, especially after the 30th year. This tendency is also evident in our respondents, however with a slight increase in the period of young adulthood for men. This deviation may have been hidden by the high representation of women in their sample (68%). Differences between people aged less than 26 and adults could also be results of the differences in places visited on the internet. Younger adults and adolescents spend more time with non-job-related communication, and we also need to take into account free-time activities. While adolescents and young adults spend more time entertaining themselves, individuals over 30 more often spend their time with founding families, developing their careers etc.

Caspi and Gorsky (2006) also claim, quite interestingly, that online lying is considered a widespread phenomenon, something 73% of their respondents agree with. Authors have two explanations for the discrepancy between the documented ratio of lying and the perceived wide spread of lying on the internet. One reason is, they believe, that the respondents may have experienced being lied to in some damaging manner, which could have lead to an over-generalization of this phenomenon. The other explanation could be that such a negative picture of the internet is the result of its presentation as a highly unstable environment by the media. Such a negative presentation of internet environments can influence the behavior or expectations of those visiting these environments.

If we focus on the differences between the lying of men and women in the environment of the internet, Caspi & Gorsky (2006) identified no statistically relevant differences. The results of our study correspond with the concluding notes of these authors. In our case, we did notice a difference on a significance level of p < 0,05, this is however insignificant with respect to the number of respondents. Similar results are also noted by e.g. Whitty and Gavin (2001) and Whitty (2002), however their findings are on a similarly low significance level. Additionally, both these studies were primarily focused on the area of chat rooms, the first even more specifically emphasized the study of relations in chat rooms. The differences between the frequency of lying between men and women aged 19-26 are quite interesting. While men seem to keep their tendency to lie up until they become adults, women have a gradual decrease in theirs.

Substantial differences are noted between recipients of lies. As far as lying to individuals of the opposite gender goes, we found no significant differences between men and women. Women lie more often to other women, while men lie as often to both men and women. One of several motives is making the liar look more attractive. While lying to a person of the opposite gender occurs most often to increase one’s own (sexual or partner) appeal, lying to “everyone” has a much broader range. Here one’s appeal can be increased as a whole, not just on a sexual level. Individuals (seemingly) educated, financially secured etc. can be through a projection of sorts expected to also have properties linked with these positive properties (being pretty, good etc.), leading to an idealization of the object. The other possible cause for lying could be entertainment.

Our results partially correspond with the conclusions on lying about one’s age (Caspi & Gorsky, 2006; Gross, 2004; Valkenbur, Schoulen, & Peter, 2005; Whitty, 2002), where younger users lie more often than older ones. Direct comparison is however not completely possible. Whitty included all ages between 21 and 50 in the “older” age category, whereas our results (as well as Caspi’s and Gorsky’s) indicate that there are significant differences especially between the age groups of 20-30 and above 30. Caspi and Gorsky used age categories similar to ours, our results differentiate from theirs in comparable categories in ranges between 7.7% and 3.6%.

Playing different identities is, based on Caspi and Gorsky (2006), often a motive for gender swapping. If we look at results for individual environments, it is noticeable that this phenomenon is very rare (peaking in computer games with a 6% rate for men) and almost entirely the domain of men. These results correlate very well with the findings of Whitty (2002). We believe that a higher occurrence of this phenomenon in this almost purely masculine environment is caused by a higher motivation from potential benefits for women in this environment (help with in-game tasks, in-game money loans or donations etc.). A small exception is the age group of women aged 12-18 in chat rooms, where the expected reason would be playing another identity.

Lying about employment, education and income occurs, based on our results, most often in the group of men (fully in agreement with the study of Whitty (2002) aged 19-26 in the environment of chat rooms, which is typical for creating relationships. Caspi and Gorsky (2006) relate lying about employment etc. with playing other identities, which is perceived as a game. To a much smaller extent, they believe lying occurs to increase one’s attractiveness or status. This is why we believe that lying about the aforementioned areas has a direct link with increasing the man’s social attractiveness in this age with a notable influence of stereotype sexual patterns. A pursuit of one’s attractiveness is also related to lying about one’s physical appearance, which is most prevalent in the age groups between 12 and 26 years of age.

For various age groups we can thus differentiate various areas about which they feel the need to lie – for the youngest group it is age and physical appearance (most often in chat rooms, especially those designated for meeting people). The middle group has shifted its priorities towards the “stable manifestations of adulthood” – education, income. This is true especially for men; women do not feel the urge to lie about their age, however they do tend to lie about their appearance sometimes. For the oldest age group, hot topics in lying include age, income for men and attractiveness for women.

The frequency of lying in various environments is influenced by several effects. One of these is the frequency of individuals in various age groups actually visiting these environments, and also how much time they spend here. This should, e.g. in the case of discussion forums, also affect the degree of one’s identification with a group and adherence to certain norms. In discussion forums however we have paradoxically found a relatively high frequency of lying, especially for the youngest users. Additionally, lying about one’s age could have a completely different motivation when compared to lying about one’s age in chats – age can significantly affect the weight of arguments in discussions. The second is the subject or theme of a given internet environment. Chat rooms and IM are typical representatives of “informal communication”, often serving for entertainment or meeting new people. In such environments, lying is often much easier than e.g. on discussion forums. Lying in computer games is very interesting for its unique (yet still quite rare) phenomenon of gender-swapping of boys. A relatively high unreliability of e-mails found in our study contrasts the findings of Jeffrey et al. (2002), as well our expectations – we thought that especially for adolescents and younger adults the e-mail represented a more formal means of communication than e.g. IM.

A certain limitation of the study is also the neglecting of social networks, however during this research only an insignificant percentage of users in the Czech Republic utilize social networks. Social networking has increased in popularity only this year.

Concluding notes

Our results indicate that the internet as a whole has no or minimal effect on the subjects which adolescents or young adults deal with. Lies appear in all environments with various frequencies, and lying itself is thus influenced mostly by the topics usually discussed in these environments. For adolescents and emerging adults, the internet represents a place for consulting subjects important for their current stage of life. Internet environments allow to e.g. increase one’s appeal by lying about age or physical appearance, something very important for individuals in this age group. It also offers the possibility to experiment with relationships, also a key factor in this age. A clear overlap of real life into the internet is visible here – its environment forms an ideal mediating ground for tackling these subjects.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the support of the Czech Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (MSM0021622406 and 1P05ME751) and the Faculty of Social Studies, Masaryk University.

References

Amichai-Hamburger, Y., G. Wainapel, & Fox, S. (2002). On the Internet no one knows I'm an introvert: Extroversion, neuroticism, and Internet interaction. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 5, 125-128.

Bargh, J. A., McKenna, K. Y. A., & Fitzsimons, G. M. (2002). Can you see the real me? Activation and expression of the "true self" on the Internet. Journal of Social Issues, 58(1), 33-48.

Biocca, F. (2000). New media technology and youth: Trends in the evolution of new media. Journal of Adolescent Health, 27(2), 22-29.

Blinka, L. (2008). The Relationship of players to their avatars in MMORPGs: Differences between adolescents, emerging adults and adults. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 2(1). Retrieved November 2, 2009, from http://www.cyberpsychology.eu/view.php...

Blinka, L., & Smahel, D. (2009-in press). Fourteen is fourteen and a girl is a girl: Validating the identity of adolescent bloggers. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 12(6).

Bowker, N. & Tuffin, K. (2003). Dicing with Deception: People with Disabilities' Strategies for Managing Safety and Identity Online. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 8 (2). Retrieved September 20, 2008, from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol8/issue2/bowker.html

Caspi, A., & Gorsky, P. (2006). Online Deception: Prevalence, Motivation, and Emotion. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 9, 54-59.

Cornwell, B., & Lundgren, D. C. (2001). Love on the Internet: Involvement and misrepresentation in romantic relationships in cyberspace vs. realspace. Computers in Human Behavior, 17(2), 197-211.

Curtis, P. (1992). Mudding: Social phenomena in text-based virtual realities. Paper presented at the DIAC92. Retrieved March 10, 2008 from ftp://ftp.lambda.moo.mud.org/pub/MOO/papers/DIAC92.txt

DePaulo, B. M., & Kashy, D. A. (1998). Everyday lies in close and casual relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(1), 63-79.

DePaulo, B. M., Kirkendol, S. E., Kashy, D. A., Wyer, M. M., & Epstein, J. A. (1996). Lying in everyday life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 979-995.

Döring, N. (2002). Personal home pages on the Web: A review of research. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 7(3). Retrieved February 13, 2009 from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol7/issue3/doering.html

Ekman, P. (1997). Lying and deception. In Stein, N. L., Ornstein, P. A., Tversky, B. & Brainerd, C. (Eds.), Memory for Everyday and Emotiaonal Events (pp.333-347). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Retrieved June 19, 2008 from http://www.paulekman.com/pdfs/lying_...

Galácz, A., & Smahel, D. (2007). Information Society from a Comparative Perspective: Digital Divide and Social Effects of the Internet. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 1(1). Retreived January 9, 2009 from http://www.cyberpsychology.eu/view.php...

Griffiths, M. D., Davies, M. N. O., & Chappell, D. (2004). Demographic factors and playing variables in online computer gaming. Cyberpsychology & Behavior 7, 479-487.

Gross, E.F. (2004). Adolescent Internet use: What we expect, what teens report. Applied Developmental Psychology, 25, 633-649.

Jeffrey, T. H., Jennifer, T. S., & Thompson, R. (2004). Deception and design: the impact of communication technology on lying behavior. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems.

Joinson, A. N., & Dietz-Uhler, B. (2002). Explanations for the perpetration of and reactions to deception in a virtual community. Social Science Computer Review, 20(3), 275-289.

Kashy, D. A., & DePaulo, B. M. (1996). Who lies? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 1037-1051.

Lea, M., & Spears, R. (1995). Love at first byte? Building persona l relationships over computer networks. In J. T. Wood, & S. W. Duck (Eds.), Understudied relationships: off the beaten track (pp. 197–233). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

McKenna, K. Y. A., Green, A. S., & Gleason, M. E. J. (2002). Relationship formation on the Internet: What's the big attraction? Journal of Social Issues 58(1), 9-31.

Poster, M. (1997). Cyberdemocracy: The Internet and the public sphere. In D. Holmes (Ed.), Virtual politics: Identity and community in cyberspace (pp. 212 - 228). London: Sage.

Reicher, S. (1987). Changing conceptions of crowd mind and behavior - Graumann,Cf, Moscovici, S. British Journal of Psychology, 78, 273-274.

Reid, E. M. (1991). Electropolis: Communication and Community on Internet Relay Chat. Inzertek 3(3), 7-15. Retrieved April 26, 2008 from http://www.irchelp.org/irchelp/misc/electropolis.html

Reid, E. (1995). Virtual worlds: culture and imagination. In S.G. Jones (Ed.), CyberSociety: computer-mediated communication (pp. 164–183). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rheingold, H. (1993). The Virtual Community. [Electronic version] The MIT Press. Retrieved January 11, 2008 from http://www.rheingold.com/vc/book

Rollman, J. B., Krug, K., & Parente, F. (2000). The chat room phenomenon: Reciprocal communication in cyberspace. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 3, 161-166.

Rowatt, W. C., Cunningham, M. R., & Druen, P. B. (1999). Lying to get a date: The effect of facial physical attractiveness on the willingness to deceive prospective dating partners. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 16(2), 209-223.

Siibak, A. (2009). Constructing the self through the photo selection - visual impression management on social networking websites. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 3(1). Retrieved October 3, 2009 from http://www.cyberpsychology.eu/view.php?...

Turkle, S. (1994). Constructions and reconstructions of self in virtual reality: Playing in the MUDs. Mind, Culture and Activity, 3, 158-167. Retrieved July 2, 2008 from http://mit.edu/sturkle/www/pdfsforstwebpage/...

Tyler, J. M., & Feldman, R. S. (2004). Truth, lies, and self-presentation: How gender and anticipated future interaction relate to deceptive behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34, 2602-2615.

Valkenburg, P.M., Schoulen, A.P., & Peter, J. (2005). Adolescents´ identity experiments on the internet. New Media & Society, 7, 383-402.

Wallace, P. (1999). The Psychology of the Internet. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Whitty, M., & Gavin, J. (2001). Age/sex/location: Uncovering the social cues in the development of online relationships. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 4, 623-630.

Whitty, M. T. (2002). Liar, liar! An examination of how open, supportive and honest people are in chat rooms. Computers in Human Behavior, 18, 343-352.

Whitty, M. T. (2008). Revealing the 'real' me, searching for the 'actual' you: Presentations of self on an internet dating site. Computers in Human Behavior 24, 1707-1723.

Correspondence to:

Štěpán Konečný

Faculty of Social Studies

Instute for Research on Children, Youth and Family

Joštova 10

60200 Brno

The Czech Republic

Phone: +240 549 49 4169

E-mail: skonecny(at)fss.muni.cz