How do consumers perceive the reliability of online shops?

Tomomi Hanai1, Takashi Oguchi2

Abstract

Keywords: consumer behavior, trust, reliability, information, online shop

Introduction

The term “brand” originally refers to a “description or trademark which indicates a type of product made by a particular company.” However, in modern Japanese society it refers to those branded products that are perceived to have a higher quality than other similar products. Thus, the term “brand” authenticates that its products belong to a high-class, and the people who possess these branded products are regarded as “exclusive people” through the “basking-in-reflected glory process” (Cialdini, Borden, Thorne, Walker, Freeman, & Sloan, 1976). The branded products interest female young people and recently they have been more inclined to purchase them via online shopping. However, they tend to refrain from purchasing these products via online shopping due to their distrust of it. Consequently, it becomes more and more important to analyse what kind of information contributes to trust formation in online shopping.

Female Undergraduate Students’ Attitudes toward Branded Products

First, we introduce several surveys for determining the attitude towards, and ownership of, branded products among female young people, especially female undergraduate students in Japan, who are the target group of this study. Infoplant (2007) showed that nearly half of all people are interested in some branded products. Although branded products generally attract the attention of various kinds of people, young females are especially interested in branded products. Infoplant (2007) revealed that more than 60% of females under 20 years of age and nearly 80% of females in their twenties have purchased some branded products. Furthermore, the percentage of people who usually buy new branded products is about 20% among females under 20 years of age and more than 10% in females in their twenties.

Tsukamoto, Ochiai, and Komuro (2005) also reported attitudes towards and ownership of branded products among undergraduate students at a local university, female students in a two-year college in Tokyo, and female students in a professional school in Tokyo. According to their report, 66% of females and 39% of males at a local university were interested in branded products. About 73% of the female students in the two-year college in Tokyo and 78% of students in the professional school stated that they were interested in some branded products. Thus, overall, the male undergraduate students are less interested in branded products; however, females, particularly the females in Tokyo, exhibit a significant interest in branded products. However, the majority of opinions about online shopping for branded products were negative. About 39.1% of the respondents stated that “It is unsure whether a product fits with my preference until I examine it with my hands,” and 29.8% stated that “A product is unreliable.”

These surveys reveal that female undergraduate students are generally very interested in branded products. However, they tend to refrain from purchasing branded products online due to their distrust of online shopping.

Why People Distrust Online Shopping for Branded Products

Next, we investigate why people tend to distrust purchasing branded products online from a viewpoint of “perceived risk.” Perceived risk is the risk that consumers subjectively perceive (cf. Jacoby & Kaplan, 1972; Yates & Stone, 1992). Jacoby and Kaplan (1972) classify risks, perceived by consumers when they purchase diverse products, from life insurances to cards, into “financial risk,” “functional risk,” “physical risk,” “psychological risk,” and “social risk.”

In the case of purchasing branded products, it is often important to tell the real from the fake. In other words, purchasing branded products involves risk, which is perceived risk. Since branded products are relatively expensive compared to other products, if a consumer purchases a counterfeit by mistake they will suffer significant financial damage. Thus, branded products involve financial risks. In addition, since the possession of branded products implicitly refers to “exclusive people” in modern Japanese society. Known as “basking-in-reflected glory process” (Cialdini, Borden, Thorne, Walker, Freeman, & Sloan, 1976), people are inclined to enhance their self-esteem through association to related people or items. Through the basking-in-reflected glory process, it is possible to speculate that people who possess branded products are themselves regarded as “exclusive people.” If those people purchase a counterfeit by mistake, they will not only be negatively evaluated by others but it will also hurt their self-esteem. Thus, branded products involve both psychological and social risks. Although the physical risks are dependent on the nature of product, the functional risks might be moderately high because branded products are expected to be of high quality.

Consumers generally perceive diverse risks in the consumption process of branded products. One of the essential factors that can overcome these perceived risks is trust. Trust is defined as a person’s expectation of the other’s cooperative behavior in situations where it is possible to suffer some damage if the other behaves selfishly (Yamagishi, 1998). In the case of branded products, if a shop dealing with branded products sells counterfeits consumers who purchase these products will suffer serious damage as previously described. Because of this, consumers will buy branded products from a shop that they believe does not provide counterfeits. In other words, it is necessary for consumers to trust a shop before they decide to purchase branded products.

The importance of trust is not only emphasized in the consumption process of branded products but also discussed by various researchers; research examining the importance of trust in online shopping continues to increase. Buttner and Goritz (2008) discuss that trustworthiness promotes both intention to buy and actual financial risk for medical goods. Riegelsberger, Sasse, and McCarthy (2007) point out the importance of trust formation in mediated transactions such as online shopping. In the mediated transaction it is necessary to match the consumer’s intention of buying a product with the shop’s intention of selling it. Next, the consumer determines the shop’s reliability based on the information transmitted by the shop. If the consumer believes he or she is able to trust the shop then the consumer shows his or her intention of buying the product to the shop and the shop responds by selling it. If the consumer judges that he or she is unable to trust the shop the consumer withdraws and the transaction fails. During the transaction the properties that induce consumer’s trust are known as the “trust warranting properties,” the behavior and nature of a shop, which is a trustee (Bacharach & Gambetta, 2003). If these trust warranting properties are apparent then the consumers can trust the shop and show their intention of purchasing products without any problems.

However, in online shopping it is difficult to transmit these trust warranting properties from an online shop to its consumers due to the spatial and time discrepancies between the online shop and the consumers (cf. Daft & Lengel, 1986; Rice, 1992; Short, Eilliams, & Christie, 1976). Online shopping is somewhat different from ordinary shopping because consumers must decide to purchase products by only seeing them, they are not able to touch them. In addition, sometimes online shops and consumers transact with one another with a time lag, thus if consumers have questions or are anxious about something during online shopping they are not able to get the online shop’s support. Furthermore, once the consumer despairs in the online shop or the online shop’s support, it is likely to escape from that relationship and move to another online shopping website. This results in difficulty in developing a close and continuous relationship between an online shop and its consumers.

In summary, currently many online shops confront the difficulty of transmitting trust warranting properties to the consumers. There are several researches examining the role of trust in online shopping, they mainly focus on products with a low level of perceived low-risk products (c.f., Buttner & Goritz, 2008). Although we agree that this kind of adversity is suffered by almost all types of online shops. The online shops which deal with branded products seem to regard it seriously because their consumers often encounter a high level of perceived risk. This suggests that it is necessary for online shops selling branded products to investigate how to remove their consumers’ distrust.

How to Confront Distrust of Online Shopping for Branded Products

In this section we examine methods for reducing distrust in online shopping by both the online shop and the consumers. The perceived risk promotes people who feel it to engage in information seeking. Ikenoue and Kobayashi (1994) point out three ways to reduce the level of perceived risk: “active information seeking,” “deep consideration prior to decision making” and “development of brand loyalty.” Consumers usually try to seek, collect, and examine related information as much as possible. Thus, consumer behavior for products which contain the high level of perceived risk involves active and well-considered information seeking behavior. Suzuki (1993) also demonstrated that consumers were inclined to seek information aggressively when they purchased products which were perceived as requiring carefull decisions before purchase. Consequently, it is expected that consumers engage in active information seeking to reduce their perceived risk. More specifically, this view point suggests that online shops need to supply the specific and useful information its consumers request.

On the other hand, online shops have also made several attempts to convey clear and trustworthy messages regarding their products and themselves. There has been a focus on the development of interfaces which effectively transmit the online shop’s trust warranting properties. For example: affiliations with reliable organizations (Ratnasingam & Pavlou, 2004); presentation of descriptive explanations about products (Nielsen, Molich, Snyder, & Farrell, 2000); usability (Lee & Turban, 2001); presentation of security information (Nielsen et al., 2000); and others (cf. Riegelsberger et al., 2007). Bansal, Mcougall, Dikolli, and Sedatole (2004) discuss the behavioral outcomes of a consumer’s satisfaction with an online shop, exploring that satisfaction with the online shopping website through how it enhances purchasing and browsing behaviors such as its selection, design and maintenance. Hanai, Miura, Harashiam, and Oguchi (2007) also emphasize the importance of website design for promotion of products sold in an online shopping website. These findings suggest that it is beneficial for promoting consumer’s behavior to design trustful online shopping websites.

In summary, we examine the kind of information that contributes to trust formation in online shopping by focusing on the online shops dealing with branded products, where trust formation in online shops or products might be highlighted to a greater extent.

Method

Pre-Survey: Assessment on the Descriptive Information in Online Shopping Websites

Pre-Survey: Assessment of the Descriptive Information in Online Shopping Websites In this study we examine online shopping websites for branded products, particularly those that deal with a wallet manufactured by the brand “Louis Vuitton” and priced at between 50,000 yen and 80,000 yen. When Tsukamoto et al. (2005) asked 233 two-year college and professional female school students what they wanted to possess, about 30% of them mentioned a “Louis Vuitton” wallet. Thus, it was naturally assumed that the female undergraduate students, who participated in this experiment, are generally interested in and think of purchasing branded products.

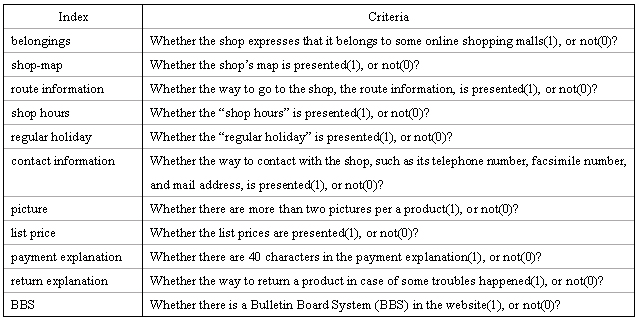

We extracted online shopping websites for branded products via one of the most popular search engines, and there were 20 online shops that met all of the above criteria. Thus, these 20 online shops were assessed according to descriptive information provided in the online shopping websites, as presented in Table 1. These 11 criteria based on the Web Advertising Bureau (2002, 2003).

Participants

Twenty seven female undergraduate students were recruited to evaluate the trustworthiness of the target online shopping websites. The participants were those who had usually used the Internet.

Procedure

We classified the 20 online shops into three categories, that is, we chose six or seven websites per group and randomly assigned them to the participants. In other words, one online shopping website was evaluated by about nine participants. The following constitutes the evaluation items.

Reliability of the Online Shops

The reliability of the online shops was evaluated by presenting six items as follows. “The shop is reliable,” “I want to buy some products from the shop,” “The shop creates a good impression,” “I want to access the shop’s website after the experiment,” “I wonder about the authenticity of the products,” and “I am concerned whether the payment would involve any trouble.” These items were rated on a scale, ranging from “completely disagree (1)” to “completely agree (5).” These items were made by the authors and a female undergraduate student.

Images of the Online Shops

The images of the online shops were presented by 15 SD items (Iwashita, 1983); “unsophisticated (1)-sophisticated (5),” “insipid (1)-cheerful (5),” “sober (1)-showy (5),” “hard (1)-soft (5),” “narrow (1)-broad (5),” “unsteady (1)-steady (5),” “small (1)-large (5),” “simple (1)-complex (5),” “static (1)-dynamic (5), “general (1)-characteristic (5),” “weak (1)-strong (5),” “nervous (1)-easygoing (5),” “unfamiliar (1)-familiar (5),” “rough (1)-delicate (5),” and “dark (1)-bright (5).”

Results

Assessment of the Descriptive Information on the Online Shopping Websites

The frequency table of the assessments of descriptive information on the online shopping websites is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Frequency Table of Assessment on Descriptive Information on Online Shopping Website

In order to classify the assessments of the descriptive information on the online shopping websites, a principle component analysis was performed. The results of this analysis are shown in Figure 2, where component 1 scores are represented in the horizontal axis and component 2 scores, in the vertical axis. The items to the right of Figure 2 represent information about the shop (e.g., “shop-map,” “route information,” “regular holiday,” and “shop hours”). Thus, the component 1 scores refer to the extent of information provided about the shop. On the other hand, the items above Figure 2 provide information about the procedures and services of the shop (e.g., “belongings,” “payment explanation,” “return explanation,” and “BBS”). Thus, the component 2 scores refer to the extent of information provided about the procedures and services of the shops.

Figure 2: Classification of Assessment on Descriptive Information on Online Shopping Website

Evaluations on the Reliability of the Online Shops

As a result of the factor analysis using the principal factor method on the six items on the reliability of the online shops, one factor was extracted (contribution = 56.18%). We calculated their total score that is known as the “reliability score.” The Cronbach’s α was .88.

Next, the averages of the reliability scores per online shop were calculated, and the online shops were classified into the top 10 and the bottom 10 online shops. The top 10 online shops were termed as “high reliable shops” and the bottom as “low reliable shops.” The average of the reliability scores for the high reliable shops (M = 2.98, SD = 0.29) was significantly higher than that of the low reliable shops (M = 2.47, SD = 0.20; F(1,18) = 21.56, p < .001).

Evaluation of the Images of the Online Shops

As a result of the factor analysis using the principal factor method and promax rotation on the 15 items of the images of the online shops, three factors was extracted (cumulative contribution = 59.60%). The first factor consisted of six items that included “unsophisticated (1), sophisticated (5),” “insipid (1), cheerful (5),” “sober (1), and showy (5).” Since these items showed the extent to which the online shop was trendy or progressive, the first factor was termed “progressiveness.” The second factor consisted of five items that included “small (1), large (5),” “simple (1), complex (5),” “static (1), dynamic (5).” Since these items indicated the manner in which the online shop was intricate, the second factor was termed “intricacy.” The third factor consisted of four items that included “nervous (1), easygoing (5),” “unfamiliar (1), familiar (5),” and as these items showed how the online shop exhibited a friendly image the third factor was termed “friendliness.” The total score was calculated per factor, and each score was then named as follows: “progressiveness score,” “intricacy score,” and “friendliness score.” The Cronbach’s α for each factor was .87, .76, and .67. Although the third factor’s reliability was a little low, it was recognized that the overall reliability was enough.

Next, the averages of progressiveness scores per online shop were calculated, and the online shops were classified into a top 10 and a bottom 10 of online shops. The top 10 online shops were termed as “progressive shops” and the bottom ones as “conservative shops.” An average of the progressiveness scores for the progressive shops (M = 3.26, SD = 0.21) was significantly higher than the that for the conservative shops (M = 2.80, SD = 0.23; F(1,18) = 21.53, p < .001). Furthermore, we calculated and classified the 20 online shops on the basis of the intricacy and friendliness scores. Based on the intricacy score, the top 10 online shops were termed “intricate shops” and the bottom ones were termed “plain shops.” An average of the intricate scores for the intricate shops (M = 3.33, SD = 0.15) was significantly higher than that of the plain shops (M = 2.89, SD = 0.17; F(1,18) = 38.94, p < .001). In addition, based on the friendliness score, the top 10 online shops were termed “friendly shops” and the bottom ones were termed “unfriendly shops.” An average of the friendliness scores for the friendly shops (M = 3.40, SD = 0.16) was significantly higher than that of the unfriendly shops (M = 2.96, SD = 0.20; F(1,18) = 28.77, p < .001).

Relationships between the Assessment of the Descriptive Information and Reliability and Images of the Online Shops

For investigating the relationships between the assessment of descriptive information and reliability of the online shops, we examined the differences between the high reliable shops and the low reliable shops with respect to component 1 and component 2 scores. The component 2 scores of the high reliable shops (M = 0.54, SD = 0.89) were significantly higher than that of the low reliable shops (M = -0.54, SD = 0.88) in terms of the extent of information about their procedures and services (F(1,18) = 7.44, p < .05). However, there was no difference in the component 1 scores between the high reliable and low reliable shops in terms of the extent of information provided.

In addition, we examined the relationship between the assessment of the descriptive information and images of the online shops. Although no differences existed in the progressiveness and friendliness scores, the plain shops (M = 0.44, SD = 1.07) were marginally higher than the intricate shops (M = -0.44, SD = 0.81) in component 1 scores in terms of the extent of information provided about the shop (F(1,18) = 4.28, p < .10). However, in component 2 scores in terms of the extent of information provided about the shop no difference was found between them.

Figure 3: Relationships between Assessment of Descriptive Information and Reliabilities and Images of Online Shop

Discussion

Information Transmitting Reliability

The results of the study reveal that the information about the procedures and services of online shops, which includes the concrete information necessary for the consumption process, such as payment information and return information, heightens the reliability of these shops. As the transactions of online shops are different from that of real shops, online shopping requires time and spatial intervals for transactions between consumers and shops. In the transactions of real shops, consumers and shops exist and transact with each other in the same place at the same time. This enables consumers to inquire about any problems or worries they have on the spot. Shops generally gain consumers’ trust by responding to consumers’ inquires properly. However, if shops behave towards consumers in an improper manner, they will lose consumers’ trust and the transactions will fail. In this manner trust between consumers and shops is gradually formed, while being in real time communication.

However, when time and spatial intervals exist between consumers and shops during transactions, such as are found in online shopping, consumers cannot ask any questions or address their worries as they can on the spot to the shops. Although the shops provide some means of communication to their consumers for inquiries, such as e-mails or telephones, many consumers withdraw from transactions instead of inquiring, and shift to other online shops. On the Internet consumers are able to search for other online shops; thus, without moving away from their PCs, they can easily go to another online shop and begin another transaction if they experience a problem. Due to this, the possibility of consumers’ moving to other transactions is higher in online shops than real shops. To avoid this serious problem, it is necessary for online shops to present enough information to answer all consumer questions in advance. This may help consumers in perceiving the reliability of an online shop and reduce the possibility of them shifting to other transactions.

In addition, the information about the procedures and services of online shops heightens their image as well as their reliability. The online shops which include a lot of information regarding procedures and services are regarded as “friendly” shops. It might imply instinctive characteristics for the information about the procedures and services of online shops. Because services are usually provided by shop staff, information provided about them may invoke in the consumer images of friendly and kind staff. It is thought that presenting information about the procedures and services creates an affinity with consumers.

According to various earlier studies, the presentation of descriptive information about products helps online shops to gain the trust of consumers (Nielsen et al., 2000). This study suggests that the presentation of descriptive information about the procedures and services necessary in the consumption process is also required.

Suggestion for the Field of Marketing

This study has great potential for the field of marketing. Several researchers have pointed out that excessive information pressurizes people. For example, Sundar, Hasser, Kalyanaraman, and Brown (2003) examined how impressions held by people for a candidate in a selection changed after the operation of his website’s interactivity. As a result, although people who are less interested in politics had better impressions of the candidate in proportion to the website’s interactivity. The people who were interested in politics evaluated the candidate in the website at a moderate interactive level. This might be due to the “interactivity paradox” (Bucy, 2003).

These insights lead to an important idea, that it is essential for a shop to select the most demanded information and present it to the consumer to gain trust. People’s capacity to process information is limited and the more interested they are, the more stressed they become: ironically. This study’s results provide a proposal for a useful technique of presenting information. According to the results it is effective for online shops to attempt to present information on procedures and services which includes the concrete information necessary for the consumption process, in order to gain or build consumers’ trust.

In modern society, people are able to interact with others across the border and it has changed the form of the market. One aspect of this change is the promotion of online shopping. In Japan, 39.0 % of Internet users who are over six years old have purchased something on Internet in just the past year (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, 2008). In such an environment the form of the market becomes more and more open-toward and needs more and more trust (Yamagishi, 1998). Furthermore, people who are able to trust others properly are sensitive with trust-related information (Yamagishi, 2003). These trends suggest investigations into what kind of information is related to trust are important and necessary.

Limitations and Future Implications

The implications of this study’s results are limited in certain aspects. This study focuses on the online shops of branded products which are considered interesting by young women. Therefore, we may not reject the possibility that the results and implications of this study can only be applied to the highly committed consumer. The products, which are perceived to have high risks, such as branded products, encourage consumers’ information search process (Suzuki, 1993). Therefore, it is necessary to clarify their universality; in other words, it is essential to examine whether people who are less committed to the target products require information about procedures and services and whether any online shop that deals with products other than branded products requires similar information. Past experiences of online shopping might have an effect on consumers behaviour online. Consumers stock their consumer experiences from every purchase and decide which products they buy based on their experiences. It is natural to expect consumers who have purchased products, such as branded products, online to pay attention to different information from those who have not experienced it. In addition, there are also cultural differences in trust and this might have an effect on the results of the study. For example, Americans are more inclined towards risk taking and trust formation than Japanese (Cook, Yamagishi, Cheshire, Cooper, Matsuda, and Mashima, 2005). It might be possible to find some cultural differences in the aspects of information people evaluated as trust-related.

Konradt, Wandke, Balazs, and Christophersen (2003) developed the Usability Questionnaire for Online Shops to measure usability. They classified the usability of online shops into seven components; general usability, accessibility of general conditions, product search, shopping-basket handling, process of ordering, product overview, self-descriptiveness and product characteristics. In addition, they found that usability has the greatest impact in online shopping. This suggests that it is more beneficial to address this issue comprehensively, which is to say approaching from both usability and trust formation.

Finally, this study focus on what kind of information should be presented on online shopping websites, that is to say website design and content. Other factors which are pointed out as promoting online shopping such as affiliations with reliable organizations (Ratnasingam & Pavlou, 2004), presentation of descriptive explanations about products (Nielsen, Molich, Snyder, & Farrell, 2000), usability (Lee & Turban, 2001), and presentation of security information (Nielsen et al., 2000) are not considered in this study. In addition, recent researches have emphasized the role of word-of-mouth in trust formation (cf. Murray, 1991; Kotler, 2002). The development of the Internet enables consumers to view and find other consumers’ opinions and evaluations on products. These new and current factors should be included in the future studies.

References

Bacharach, M. & Gambetta, D. (2003). Trust in signs. In K. S. Cook (Ed.), Trust in society (pp. 148-184). New York: Russell Sage.

Bansal, H. S., McDougall, G. H. G., Dikolli, S. S., & Sedatole, K. L. (2004). Relating e-satisfaction to behavioural outcomes: An empirical study. Journal of Services Marketing. 18(4), 290-302.

Bucy, E. P. (2003). The interactivity paradox: Closer to the news but confused. In E. P. Bucy & J. E. Newhagen (Eds.), Media access: Social and psychological dimensions of new technology use (pp. 47-72). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Buttner, O. B. & Goritz, A. S. (2008). Perceived trustworthiness of online shops. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 7(1), 35-50.

Cialdini, R. B., Borden, R. J., Thorne, A., Walker, M. R., Freeman, S., & Sloan, L. R. (1976). Basking in reflected glory: Three (football) field studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34, 366-375.

Cook, K. S., Yamagishi, T., Cheshire, C., Cooper, R., Matsuda, M., and Mashima R. (2005). Trust building via risk taking: A cross-societal experiment. Social Psychology Quarterly, 68(2), 121-142.

Daft, R. L. & Lengel, R. H. (1986). Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Marketing Science, 32, 554-571.

Hanai, T., Miura, Y., Harashima, M., & Oguchi, T. (2007). Impact of the inspection of the Onsen websites on hope of visiting, recommended hope, and spot images. Coming of the Asian Waves: Tourism & Hospitality: Education & Research (Proceedings of Asia Pacific Tourism Association 13th Annual Conference), CD-ROM.

Ikenoue, N. & Kobayashi, I. (1994). Introduction to consumer psychology. Tokyo: Chuokeizai-sha.

Infoplant (2004). “Louis Vuitton,” “Gucci,” and “Hermes” is the top 3 brand-name products men and women prefer. Retrieved May 7, 2009, from http://www.yahoo-vi.co.jp/research/photo/00380.pdf

Iwashita, T. (1983). Measurements on images through SD method: Understanding and procedure manual. Tokyo: Kawashima Shoten.

Jacoby, J. & Kaplan, L. B. (1972). The components of perceived risk. In M. Venkatesan (Ed.), Proceedings of Association for Consumer Research 3rd Annual Conference (pp. 382-393).

Konrdt, U., Wandke, H, Balazs, B., & Christophersen, T. (2003). Usability in online shops: Scale construction, validation and the influence on the buyers' intention and decision. Behaviour & Information Technology, 22(3), 165-174.

Kotler, P. (2002). Marketing management. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Lee, M. K. O., & Turban, E. (2001). A trust model for consumer Internet shopping. International Journal of Electronics Commerce, 6(1), 75-91.

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (2008). Communication usage trends report 2007. Retrieved May 7, 2009, from http://www.johotsusintokei.soumu.go.jp/statistics/pdf/HR200700_001.pdf

Murray, K. B. (1991). A test of services marketing theory: Consumer information acquisition activities. Journal of Marketing, 55, 10-25.

Nielsen, J., Molich, R., Snyder, S., & Farrell, C. (2000). E-commerce user experience: Trust. Fremont, CA: Nielsen Norman Group.

Ratnasingam, P., & Pavlou, P. A. (2004). Technology trust in internet-based interorganizantional electronic commerce. Journal of Electronic Commerce in Organizations, 1(1), 17-41.

Rice, R. E. (1992). Task analyzability, use of new medium and effectiveness: A multi-site exploration of media richness. Organization Science, 3(4), 475-500.

Riegelsberger, J., Sasse, M. A., & McCarthy, J. (2007). Trust in mediated interactions. In A. Joinson, K. McKenna, T. Postmes, & U. Reips (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of Internet psychology (pp. 53-69). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Short, J., Williams, E., & Christie, B. (1976). The social psychology of telecommunications. New York: John Wiley.

Suzuki, M. (1993). The effects of perceived risk on consumers’ information-seeking. Japanese Journal of Social Psychology, 9(3), 195-205.

Tsukamoto, M., Ochiai, S., & Omuro, M. (2005). Studies on Internet shopping and weakness of undergraduates for big-name brands. Shimane University’s Bulletin (Faculty of Education), 35, 31-39.

Web Advertising Bureau (2002). Yearbook of Web marketing 2002. Tokyo: Impress.

Web Advertising Bureau (2003). Yearbook of Web marketing 2003. Tokyo: Impress.

Yamagishi, T. (1998). The structure of trust: The evolutionary games of mind. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

Yamagishi, T. (2003). Trust and social intelligence in Japan. In Frank J. Schwartz & Susan J. Pharr (Eds.), The state of civil society in Japan (pp. 281-259). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yates, J. F. (Ed.) (1992). Risk-taking behavior. New York: John Wiley.

Correspondence to:

Tomomi Hanai

Nikkei Media Marketing

Tokyo

Japan

e-mail: tomomi_ulmaridae(at)yahoo.co.jp