Exploring the Relationships among Internet Usage, Internet Attitudes and Loneliness of Turkish Adolescents

Yavuz ErdoğanUniversity of Marmara, Istanbul, Turkey

Abstract

Key words: loneliness, Internet attitudes, Internet usage, gender

Introduction

The Internet is becoming increasingly influential for many people. It seems that there is no aspect of life that the Internet does not touch. It is probably the recognition of the predominance of the Internet that has led psychologists to focus on this phenomenon (Hamburger & Ben-Artzi, 2003). Observers have noted that heavy Internet users seem to be alienated from normal social contacts and may even cut these off as the Internet becomes the predominant social factor in their lives (Beard 2002; Weiser 2001; Widyanto & McMurran, 2004; Young, 1996). Although there are a lot of, yet partly unknown, factors concerning negative effects of the internet, two main factors are especially relevant for the presented study: first there is a displacement of social activities where the individual ends up spending so much time online that he or she is unable to participate in face to face social activities. The second is the displacement of “strong ties.” That is, the quality of online relationships is of a lower quality than face to face relationships. When one engages in a large number of online relationships, these may replace the stronger face to face ones (Kraut et al., 1998; Moody, 2001).

Kraut and his colleagues (1998) claimed that greater use of the Internet was associated with negative effects on individuals, such as a diminishing social circle, and increasing depression and loneliness. Also, many quantitative studies confirmed that loneliness was associated with increased Internet use (Kraut et al., 1998; Lavin, Marvin, McLarney, Nola & Scott, 1999; Nie & Erbring, 2000; Stoll, 1995; Turkle, 1996). Internet use may be beneficial when kept to normal levels, however high levels of internet use which interfere with daily life have been linked to a range of problems, including decreased psychosocial well-being, relationship breakdown (Widyanto & McMurran 2004; Yao-Guo, Lin-Yan & Feng-Lin 2006; Whitty & McLaughlin, 2007).

Two opposing hypotheses have been proposed to explain the relationship between loneliness and Internet use: excessive Internet use causes loneliness versus lonely individuals is more likely to use the Internet excessively (Morahan-Martin & Schumacher, 2003). According to the first hypothesis time online interrupts real life relationships. Internet use isolates individuals from real world and deprives them of the sense of belonging and connection with real world contacts. Thus, loneliness can be a byproduct of excessive Internet use because users spend time online, often investing in online relationships. Additional confirmation of the adverse effect of Internet use on loneliness has been found in other studies as well. A study by Stanford University, for the Quantitative Study of Society, of a representative sample of 4113 American adults found that social isolation increases with Internet use. A quarter of the respondents who were using the Internet more than 5 hours a week believed their time online reduced their time with friends and family (O’Toole, 2000).

The second hypothesis is that lonely individuals are more likely to use the Internet excessively, because the Internet provides an ideal social environment for lonely people to interact with others. It provides not only a vastly expanded social network, but also altered social interaction patterns online that may be particularly attractive to those who are lonely (Whitty & McLaughlin, 2007). Lonely people are more likely than the non-lonely to be socially inhibited and anxious. Establishing social connections can often be quite difficult for those people who experience high levels of anxiety when in social situations. However, on the Internet, many situational factors that cause anxiety in face to-face encounters are absent. Therefore, those people who experience anxiety when communicating face-to-face might be drawn to communicate online (Bonebrake, 2002). Contrary to the idea that the Internet is a socially isolating technology, previous studies positively related the Internet to measures of social involvement (Perse & Ferguson, 2000; Shaw & Gant, 2002; Cummings, Sproull & Kiesler 2002; Oldfield and Howitt, 2004). Interestingly, after 3-year follow-up to the first study of HomeNet, Kraut and his colleagues found that almost all of the previously reported negative effects had disappeared over time (Kraut et al., 2002). Instead, higher levels of Internet use were positively correlated with measures of social involvement and psychological well-being. The Kraut et al. studies indicated that the potential for negative psychological and social consequences reduced as society became more accustomed to using the internet (Whitty & McLaughlin, 2007).

Hamburger and Ben-Artzi (2003) demonstrated that Internet use, as a function of trait variables, can decrease loneliness among users. Many studies have focused on this alternative view to examine whether lonely people access the Internet to improve their psychological well-being. Shaw and Gant (2002), for instance, found that increased Internet usage was associated with decreased levels of loneliness and depression and increased levels of social support and self-esteem. Internet activities are also known to provide support, information and opportunities for social connection to marginalized and socially isolated groups such as same-sex attracted young people (Hillier & Harrison 2007), parents of disabled children (Blackburn & Read 2005), people with social anxiety (Campbell, Cumming & Hughes 2006). More recently, Oldfield and Howitt (2004) found that those who spent more time on Internet were less likely to be lonely.

As previously mentioned, there are conflicting views on the relationship between the Internet use and loneliness. Some experts claimed that increased Internet usage is associated with decreased levels of loneliness (Shaw & Gant, 2002; Hamburger & Ben-Artzi, 2003; Oldfield & Howitt, 2004) while the others demonstrated that loneliness is positively related with increased Internet use (Kraut et al., 1998; Lavin et al., 1999). One of the main reasons for these conflicting views is cultural differences. For instance, the Turkish are generally sociable, and prefer face to face communication (Deloitte, 2008; Erdoğan, 2007; Savran, 1993). Physical presence and visual cues play as an integral role in establishing relationships. Because of the anonymous nature of the Internet, many experience difficulties in making friendships, rather than using it as an alternative to offline friendships. Thus, they do not make close connections online that they do in the offline environments. In regards to these perspectives, this study examines the relationships between Turkish adolescents’ loneliness, Internet usage and attitudes.

In addition, it has been assumed widely that males and females will differ fundamentally in the ways they view and use the Internet technology. Some researchers hypothesize that males are more comfortable with and less anxious about Internet technology. Thus, gender variable was considered as an important variable for the current study, and included as an independent variable. With these aims in mind, the following research questions were posed in the study:

1. Are there any significant relationships among Internet usage, Internet attitude and loneliness of Turkish adolescents?

2. Are there any significant predictors of Turkish adolescents’ loneliness? If so, what are they?

3. Is there a significant difference in the average weekly Internet activity (surfing the web, chat rooms, instant messaging, email and online games) hours in terms of being lonely?

4. Are there any significant differences among Turkish adolescents’ loneliness, Internet usage and Internet attitudes in terms of gender?

5. Is there a significant difference in the average weekly Internet activity hours in terms of gender?

Method

Participants

This study is a school-based study of the internet-related behaviors of adolescents in grades 9-12. The sample consisted of 1049 adolescents, and all the participants were recruited from 12 different high schools in Istanbul, in Turkey. Their ages ranged from 14 to 18 years old, and the average age of the participants was 16.46 years (SD=1.35). Green and Palfrey (2002) defines the age range 15-17 as middle adolescents. Middle adolescence is a time of physical, mental, cognitive, and sexual changes for teenagers. During this phase of development, adolescents are developing their unique personality and opinions (Green and Palfrey, 2002). For the current study, adolescents were chosen because they have access to the Internet, and therefore are more likely to be Internet users than other populations. Adolescents, especially males, are the heaviest users of the Internet and also comprise a large percentage of users of Internet sites such as Internet games. 315 (30%) of them were female, and (70%) 734 were male. Participants volunteered for the study, and reported their average weekly usage as 6.84 hours (SD=3.93). The majority of the sample (68.6%) had a computer at home, and fifty-eight percent of participants also had the Internet at home. Other points of access included local libraries and Internet cafes.

Procedure

Participants were informed on the purpose of the study and invited to participate. If they agreed to participate they signed the consent form and completed the survey. The participants filled out the survey on their own. The researcher returned after an appropriate time and retrieved the completed surveys. Participants were informed on the experiment, and any questions were answered.

Data Collection Instruments

Data were collected by using a Demographics and Internet Usage Questionnaire, an Internet Attitudes Scale and an UCLA Loneliness scale. These instruments are explained below.

Demographics and Internet Usage Questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed by the researchers, and includes questions on demographics, such as gender and age. The questionnaire addresses the average hours per week spent online as well as on certain Internet activities including surfing, chatting, instant messaging, emailing and online games.

Internet Attitudes Scale

The scale, which consists of 31 items, was designed in order to measure the Internet attitudes of the Turkish students by Tavşancıl and Keser (2002). The participants responded to the statements using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). The validity and reliability studies were carried out by Tavşancıl and Keser (2002), and the Cronbach Alpha internal consistency coefficient was found to be 0.89. The reliability study of this survey of internet attitudes was found to be 0.91.

UCLA Loneliness Scale

Loneliness was assessed using the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell, 1996). This scale includes 20 Likert-type questions on a four-point scale, with 1=strongly disagree and 4=strongly agree, and asks participants how frequently they agree with statements such as “I feel left out,” “I am no longer close to anyone,” and “My social relationships are superficial.”. The UCLA Loneliness Scale has a good reported validity and reliability with college students; the standardized item alpha was 0.92. The mean score was 37.687 (SD=8.908). Participants in the top 18% (n=186) scored 47 or higher and were considered lonely (L). They were compared with all other students (n=863) who were considered non-lonely (NL). The mean score for the lonely was 51.592 (SD=5.441). For the non-lonely, the mean score was 34.625 (SD=6.098).

Data Analysis

In this quantitative study, surveys were used to determine the role of Internet usage and Internet attitudes in Turkish adolescents’ loneliness. Firstly, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated to determine the relationships between Turkish adolescents’ loneliness, Internet usage and attitudes. Then, multiple regression analysis was performed to identify the predictors of loneliness. Secondly, multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted to compare the loneliness, Internet usage and Internet attitudes of Turkish adolescents’ in terms of gender. Lastly, MANOVA was performed again to compare the Internet usage frequency of specific activities (surfing the web, chat rooms, instant messaging, email and online games) in terms of gender and being lonely variables. For statistical analysis SPSS 13.0 package program was used.

Results

Bivariate Pearson’s correlation coefficients were run to determine the degree of relationships among the Turkish adolescents’ loneliness, Internet usage and Internet attitudes as seen in Table 1.

| Internet use | Internet attitude | Loneliness | |

| Internet use | 1.000 | 0.200** | 0.110** |

| Internet attitude | - | 1.000 | 0.052* |

| Loneliness | - | - | 1.000 |

Loneliness significantly correlates with Internet usage and Internet attitudes at the .05 level (r=0.110; p<0.01; r=0.052; p<0.05). This finding reveals that the students who have a higher frequency of Internet usage and Internet attitudes are lonelier than the others. Also, a significant correlation was observed between Internet usage and Internet attitudes (r=0.200; p<0.05). Excessive Internet use causes higher Internet attitudes. The regression analysis results are presented below in Table 2.

| Variables | B | Std. Error | t | p | |

| Constant | 56.338 | 1.660 | - | 33.943 | 0.000 |

| Internet use | 0.050 | 0.015 | 0.104 | 3.305 | 0.001* |

| Internet attitude | 0.035 | 0.035 | 0.031 | 0.983 | 0.326 |

| R=0.514 R2 =0.264; F=6.871 p<0.001 | |||||

The score on the UCLA Loneliness scale was run as the dependent variable in the regression analysis where Internet usage and Internet attitude were independent variables. This analysis yielded a significant result: F (2, 1046)=6.871, p<0.01). Independent variables together explain 26.4% of the variance in loneliness. The only variable that significantly predict the adolescents’ loneliness is Internet usage (t=3.305, p<0.01). This means that the frequency of Internet use is a significant predictor of adolescents’ loneliness.

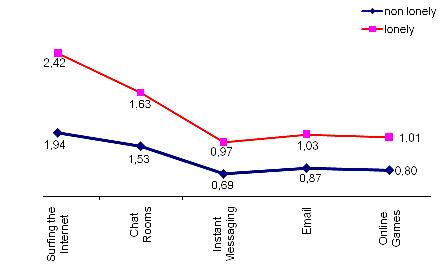

To explore further the differences between lonely and non-lonely users regarding specific Internet activities a MANOVA was performed that presented in Fig.1, and significant overall results were obtained [Wilks' λ=0.982, F (5, 1043)=3.805, p<0.05]. The lonely adolescents spent significantly more time per week on the web for surfing, instant messaging, emailing and online games than the non-lonely [F (1, 1047)=10.581, p<0.01; F (1, 1047)=9.812, p<0.01; F (1, 1047)=5.522, p<0.05; F (1, 1047)=5.409, p<0.05]. On the other hand, time spent in chat rooms were not significantly different for the lonely and the non-lonely [F (1, 1047)=1.096, p>0.05]. The Internet provides an ideal social environment for lonely people to interact with others. Not only does it provide a vastly expanded social network, but also it provides altered social interaction patterns online that may be particularly attractive to those who are lonely. Therefore, compared with others, lonely people are more likely to spend time for Internet activities (Morahan-Martin & Schumacher, 2003).

| Female | Male | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Internet use | 6.414 | 3.371 | 7.016 | 4.147 |

| Internet attitude | 110.047 | 20.523 | 111.365 | 17.753 |

| Loneliness | 34.685 | 8.600 | 37.975 | 8.731 |

Table 3 shows the means and standard deviations of the Internet usage, Internet attitude, and loneliness of Turkish adolescents in terms of gender. In order to investigate differences based on gender for dependent variables, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed. Gender was the independent variable where Internet usage, Internet attitude and loneliness were the dependent variables. Significant differences were obtained between male and female participants for the dependent variables [Wilks' λ=0.943, F (3, 1045)=21.126, p<0.01]. These were observed in two categories: male adolescents reported more Internet usage frequency [F (1, 1047)=5.171, p<0.05] and they were significantly lonelier than female adolescents [F (1, 1047)=53.683, p<0.01]. However, Internet attitudes of the male and female adolescents did not differ significantly [F (1, 1047)=1.103, p>0.05].

Fig.2 shows the mean scores of Internet activity frequencies in relation to gender. In order to investigate differences in gender Internet activity, multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was calculated which included gender (male versus female) as the independent variable and the Internet activities (surfing the web, chat rooms, instant messaging, email and online games) as the dependent variable. The results of this analysis indicate significant differences between male and female adolescents in average weekly hours spent on certain Internet activities [Wilks' λ=0.913, F (5, 1043)=19.922, p<0.01]. Significant gender differences were observed for three of the five Internet activities. Male adolescents reported a higher frequency of web surfing and online games [F (1, 1047)=11.588, p<0.01; F (1, 1047)=35.747, p<0.01]. However, females reported a higher frequency of e-mailing [F (1, 1047)=22.437, p<0.01]. No significant gender differences were found for chat rooms and instant messaging [F (1, 1047)=0.539, p>0.05; F (1, 1047)=1.426, p>0.05]. In some online activities, especially online games, status and prestige are achieved by those who have good computer skills. Additionally, these skills and the ability to master the virtual environment provide a sense of power (Morahan-Martin & Schumacher, 2000). So, males spend significantly more hours on Internet than females and their Internet attitudes are higher.

Discussion

In this study, the relationships among Internet usage, Internet attitudes and loneliness of Turkish adolescents were investigated. The results revealed that Turkish adolescents’ loneliness was associated with increased Internet use. Adolescents who reported regular Internet use for web surfing, instant messaging, emailing and online games had a significantly higher mean score of loneliness than those who did not. The results, also, indicated that the frequency of Internet use is a significant predictor of loneliness. These results are consistent with the findings of previous studies (Seepersad, 1997; Kraut et al., 1998; Lavin et al., 1999, Engelberg & Sjöberg, 2004; Whitty & McLaughlin, 2007). The HomeNet study, which reported an interesting finding regarding adolescent Internet users, also supports this argument. The results of the study showed a statistically significant relationship between age and loneliness and indicated that Internet use among adolescents resulted in larger increases in loneliness than were found for adults (Kraut et al., 1998). The Carnegie Mellon team hypothesized that this interaction might be related to developmental changes in adolescence which could cause teenagers to withdraw from social contact and to use the Internet as an escape mechanism (Kraut et al., 1998).

Kraut et al. (1998) documented that the negative effects of Internet use may results from two factors: first there is a displacement of social activities where the individual ends up spending so much time online that he or she is unable to participate in face to face social activities. The second is the displacement of strong ties. Lack of strong ties can result in loneliness and feelings of isolation (Cohen& Willis, 1985; Krackhardt, 1994; Sapolsky, 1998). That is, the quality of online relationships is of a lower quality than face to face relationships. When one engages in a large number of online relationships, they may take the place of stronger face-to-face ones (Moody, 2001). Thus, Internet use isolates individuals from the real world and deprives them of the sense of belonging and connection with real world. Kraut et al. claims that online weak ties were of poorer quality compared to the types of relationships and strong ties already established offline (Whitty & McLaughlin, 2007).

On the other hand, there is contradictory information that the Internet provides an ideal social environment for lonely people to interact with others. Not only does it provide a vastly expanded social network, but also it provides altered social interaction patterns online that may be particularly attractive to those who are lonely (Morahan-Martin & Schumacher, 2003). Shaw and Gant (2002), for instance, found that increased Internet usage was associated with decreased levels of loneliness and depression and increased levels of social support and self-esteem. Also, Kraut and his colleagues revisited their results from the first study (1998), and found that almost all of the previously reported negative effects had dissipated over time (Kraut et al., 2002). The Kraut et al. studies indicated that the potential for negative psychological and social consequences reduced as society became more accustomed to using the internet (Whitty & McLaughlin, 2007).

Perhaps loneliness has a different interpretation. But the data reported suggest that adolescent who use the Internet more showed increased loneliness. These findings could result from Turkish adolescents’ personality traits and cultural differences. Hamburger and Ben-Artzi (2000) argue that understanding the personality of the user is a crucial prerequisite in interpreting the impact of the Internet on individuals and society, because what is good for one user is not necessarily good for another (Hamburger & Ben-Artzi, 2000). In previous studies, it was confirmed that Turkish adolescents are sociable and friendly; they attach importance to being with others, and have an ability to have close relations with the others who they feel are similar to themselves (Erdoğan, 2007; Savran, 1993). Also, physical presence and visual cues play an integral role in their relationship development. Thus, they do not make the close connections online that they do in the offline environment. They feel the quality of online relationships is of a lower quality than face to face relationships, and have difficulty in making friendships rather than using online relations as an alternative to offline friendships. Accordingly, Turkish adolescents reported average time per week spent on the Internet as 6.84 hours. Compared with the previous studies, this average can be considered quite low (Hardie & Tee, 2007; Gross, Juvonen & Gable, 2002; Whitty & McLaughlin, 2007). However, some Turkish adolescents prefer online relationships, because many factors that evoke anxiety in face-to-face encounters are absent in the online environment. Those adolescents who experience anxiety when communicating face-to-face are most likely to increasingly communicate online in their leisure time. Thus, increased Internet usage might cause increased loneliness or social isolation, in which the user is deprived of human touch due to time spent on the Internet.

One other factor which was questioned in this study was gender. In the current study male adolescents reported a higher frequency of Internet usage and loneliness than females, which is consistent with the results of many studies (Odell, Korgen, & Schumacher, 2000; Schumacher & Morahan-Martin, 2001). Researchers tend to predict that males and females will differ fundamentally in the ways they view and use the Internet, hypothesizing that men will be more comfortable with and less anxious about Internet technology. It has been assumed widely that Internet is a male-biased technology, and males use the Internet more than females (Kraut et al., 1996; Odell, Korgen, & Schumacher, 2000). Morahan and Schumacher claim that males are more prone to pathological use of the internet, because they are more likely to use applications such as Internet games, netsex, and Internet gambling which are associated with more compulsive use.

A more consistent pattern that has emerged in Internet research shows that males and females use the Internet for different purposes. The results of this study indicate significant differences between males and females in the average weekly hours spent on Internet activities. Male adolescents reported a higher frequency of web surfing and online games than females. However, females reported a higher frequency of e-mailing. A possible explanation for these results might be that, as outlined in previous studies, Internet use is generally broken down into three components: communication, information gathering and entertainment. Females are most commonly associated with the communication motive and tend to use email more than males. However males are linked to information gathering and entertainment motives, reporting more frequent web surfing and use of online games. On the other hand, the use of chat rooms and instant messaging were not different in terms of gender in the current study which is consistent with some studies which have suggested that chatting is not gendered in the way email is (Shaw & Gant, 2002).

Conlusion

It is widely known that the average amount of time spent on the Internet is rapidly increasing, and that the starting age of Internet users is steadily decreasing (Kraut et al, 1998, Nie & Erbring, 2000). As time moves forward, the Internet is becoming a larger factor in the lives of people at progressively younger ages. Thus, parents, psychologists, educators, technology creators and lawmakers must become aware of the potential risks and rewards of this phenomenon (Cooper, 2003, 127).

It is important to note that the findings of the current study relate to adolescents aged 14 to 18 who live in Istanbul which is the most developed city in Turkey. These factors might limit the generalizability of the findings to a wider population, such as today’s Internet users. Future research on age differences in individuals’ preferences for using the Internet technology might prove fruitful. Consequently, because of the ever-changing nature of the Internet, what we learn today may not be valid a few years from now. Thus, ongoing research is necessary to keep abreast of it.

References

Beard, K.W. (2002). Internet addiction: current status and implications for employees. Journal of Employment Counseling, 39(2), 2-11.

Blackburn, C. & Read, J. (2005). Using the Internet? The experiences of parents with disabled children. Child: Care, Health and Development, 31, 507-515.

Bonebrake, K. (2002). College students’ internet use, relationship formation, and personality correlates. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 5, 551-557.

Campbell, A.J., Cumming, C.R. & Hughes, I. (2006). Internet use by the socially fearful: Addiction or therapy? CyberPsychology & Behavior, 9, 69-81.

Cohen, S. & Willis, T. (1985). Stress, social support and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310-357.

Cooper, N.S. (2003). The identification of psychological and social correlates of Internet use in children and teenagers . Unpublished doctoral thesis, Alliant International University, California.

Cummings, J.N., Sproull, L. & Kiesler, S.B. (2002). Beyond hearing: Where real-world and online support meet. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research and Practice, 6, 78-88.

Deloitte-Türkiye (2008). Türkiye’de İnternet kullanıcıları medyayı nasıl tüketiyor? [How internet users consume media in Turkey?] Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu. Retrieved from http://www.deloitte.com/dtt/cda/doc/content/Turkey-tr_tmt_MediaSurveyBooklet_250608.pdf .

Engelberg, E. & Sjoberg, L. (2004). Internet use, social skills and adjustment. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7, 41-47.

Erdoğan, Y. (2005). Web tabanlı yükseköğretimin öğrencilerin akademik başarıları ve tutumları doğrultusunda değerlendirilmesi [Evaluation of web based higher education according to students’ academic achievements and attitudes]. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Marmara University, İstanbul.

Green, M. & Palfrey, JS. (2002). Bright futures: Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children and adolescents. Pocket guide . Arlington, VA: National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health.

Gross, E.F., Juvonen, J. & Gable, S.L. (2002). Internet use and well-being in adolescents. The Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues, 58 (1) , 75-90.

Hamburger, Y. & Ben-Artzi, E. (2003). Loneliness and internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 19, 71.

Hardie, E. & Tee, M.Y. (2007). Excessive internet use: the role of personality, loneliness and social support networks in internet addiction. Australian Journal of Emerging Technologies and Society, 5 (1) , 34-47.

Hillier, L. & Harrison, L. (2007). Building realities less limited than their own: Young people practising same-sex attraction on the internet. Sexualities, 10, 82-100.

Kraut, R., Patterson, M., Lundmark, V., Kiesler, S., Mukopadhyay, T. & Scherlis, W. (1998). Internet paradox: A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? American Psychologist, 53, 1017-1031.

Kraut, R., Kiesler, S., Boneva, B., Cummings, J.N., Helgeson, V. & Crawford, A.M. (2002). Internet paradox revisited. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 49-74.

Krackhardt, D. (1994). The strength of strong ties: The importance of Philos in organizations. In N. Nohria & R. Eccles (Eds.), Networks and organizations: Structure, form, and action. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Lavin, M., Marvin, K., McLarney, A., Nola, V., & Scott, L. (1999). Sensation seeking and collegiate vulnerability to Internet dependence. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 2, 425–430.

Moody, E.J. (2001). Internet use and its relationship to loneliness. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 4, 393-401.

Morahan-Martin, J., & Schumacher, P. (2000). Incidence and correlates of pathological Internet use among college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 16, 13-29.

Morahan-Martin, J. & Schumacher, P. (2003). Loneliness and social uses of the internet. Computers in Human Behavior, 19, 659-671.

Nie, N., & Erbring, 1. (2000). Internet and society: a preliminary report. Stanford: Stanford Institute for the Quantitative Study of Society.

Odell, P.M., Korgen, K.O., Schumacher, P. (2000). Internet use among female and male college students. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 3, 855–862.

Oldfield, B., & Howitt, D. (2004). Loneliness, social support and Internet use . Paper presented at the conference of Internet Research 5.0: Ubiquity?, Sussex, UK.

O’Toole, K. (2000). Study offers early look at how Internet is changing daily life . Stanford News. Retrieved from www.stanford.edu/dept/news/pr/00/000216internet.html

Perse, E.M. & Ferguson, D.A. (2000). The benefits and costs of web surfing. Communication Quarterly, 48, 343-359.

Russell, D. (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66, 20-40.

Sapolsky, R. (1998). Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company.

Savran, C. (1993). Sıfat listesinin Türkiye koşullarına uygun dilsel eşdeğerlilik, geçerlilik, güvenirlilik ve norm Çalışması ve örnek bir uygulama[To realize the lingual equivalence, validity, reliability and norm studies of adjective check list adopted to Turkey]. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Marmara University, Istanbul.

Schumacher, P. & Morahan-Martin, J. (2001). Gender, Internet and computer attitudes and experiences. Computers in Human Behavior, 17, 95–110.

Seepersad, S.S. (1997). Analysis of the relationship between loneliness, copping strategies and the Internet . Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Illinois, Urbana.

Shaw, L.H. & Gant, L.M. (2002). In defense of the Internet: The relationship between internet communication and depression, loneliness, self-esteem and perceived social support. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 5, 157-171.

Stoll, C. (1995). Silicon Snake Oi l. New York: Anchor Books.

Tavşancıl, E. & Keser, H. (2002). İnternet kullanımına yönelik likert tutum ölçeğinin geliştirilmesi [Development of a Likert type attitude scale for internet using]. Journal of Educational Science and Applications, 1 (1), 79-100.

Turkle, S. (1996). Virtuality and its discontents: Searching for community in cyberspace. The American Prospect, 24, 50-57.

Weiser, E.B. (2001). The functions of internet use and their social and psychological consequences. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 4, 723-743.

Widyanto, L. & McMurran, M. (2004). The psychometric properties of the Internet addiction test. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7, 443-450.

Whitty, M.T. & McLaughlin, D. (2007). Online recreation: The relationship between loneliness, Internet self-efficacy and the use of the Internet for entertainment purposes. Computers in Human Behavior, 23, 1435–1446.

Yao-Guo, G., Lin-Yan, S. & Feng-Lin, C. (2006). A research on emotion and personality characteristics in junior high school students with internet addiction disorders. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 14, 153-155.

Young, K. (1996). Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 3, 237-244.