The Deepening of the Digital Divide in the Czech Republic

Petr Lupač1, Jan Sládek2& Philosophical Institute at the Academy of Sciences, Prague, Czech Republic

2Department of Sociology, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic

Abstract

Key words: digital divide, digital skills, information society, social inequality

1. Introduction

During the Internet hype of the nineties, the expectations of the social revolution that would be triggered by ICT diffusion were widespread. At that time, the politics in most economically developed countries were influenced by the view of the coming of the information society that was supposed to replace the ‘obsolete’ industrial society model. Especially in the US, the leading country in ICT development and diffusion at that time, the ‘shift to the Information Age’ was an integral part of the federal endeavor to strengthen its global position both economically and technologically (see e.g., Brown & Gore, 1996; Gore, 1993; “Text of President,” 1998). Various hopes and the anticipation of a radically different future as the result of ICT diffusion blossomed in public debates, attracting the attention of growing number of journalists, politicians, investors, engineers, social scientists, etc. (for general overview, see e.g., Anderson, 2005). As for the latter, the publication of Castells’ first volume of The Information Age trilogy (Castells, 1996) became the milestone marking the beginning of a very strong position for the information society concept in the sociological reflection of the unprecedented changes underway.

Having stressed the great importance of ICT access for the participation in the emerging social arrangement, some authors interested in this topic started to warn of a new problem that this development has brought along—the unequal social distribution of access to ICTs. The term “digital divide” was broadly accepted to mark this new problem. In the atmosphere of Internet hype, the digital divide issue attracted much attention, which led to strong governmental support in most economically developed countries and the growing body of respective research in social sciences. During the second half of the nineties, the studies published by National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) were the most influential. These studies highlighted the predominance of young white middle-class males from large cities among the American Internet users (NTIA, 1995; NTIA, 1999). However, as the share of those connected to the Internet increased and as the Internet bubble deflated in 2000, the digital divide has been defined as closing (cf. NTIA, 2002) and slowly disappeared from the political scope. The direct governmental funding that had supported the equalization of access chances was cut down significantly in many countries (the strongest turn was experienced in the US at the time of coming of the G. W. Bush administration) leaving the rest of the Internet’s diffusion to the market forces (Gordo, 2003, pp.169-170). The majority of countries where the Internet started to be diffused later accepted similar strategies (van Dijk, 2005, pp. 191-205).

Nonetheless, authors elaborating the issue have refused this viewpoint by emphasizing that the loudly proclaimed closure of the digital divide is unconvincingly proved 1 and that it works well—in some countries—only at the level of material access, which is only one dimension of ICT use. Two attempts were made to marshal the big number of Internet diffusion studies by creating the general multidimensional model of access: the one developed by Bucy & Newhagen (2004), and the one elaborated by van Dijk (2005).

In this article, we will try to contribute to the knowledge that has already been gathered about the issue; our basic goals are to question the evidence of the digital divide deepening in the Czech Republic and to outline the priorities of future research in the Czech Republic in order to make the picture more complete and valid. The model chosen to provide sufficient theoretical background for describing the situation will be that of van Dijk (van Dijk, 2005). Though van Dijk’s model is not flawless and has several more or less serious shortcomings2 , it represents the most comprehensive and theoretically framed attempt to grasp this complex and unprecedented phenomenon. We are also aware that the relevance of the digital divide problem itself is based on several assumptions conditioned by the acceptance of information society concept as it has been developing in social sciences since the seventies.3 We will not question here the information society concept; instead of that, we will focus on recommendations that should be followed in future research to rectify the most problematic connections between the digital divide problem and its theoretical background. The reason is that we believe in improving the model in question by way of its correction in the process of adaptation to the growing body of empirical evidence; according to us, the problems of its theoretical background are not so serious to abandon this model as such.

The article is developed in three main parts. In the first, we briefly introduce the successive model of access elaborated by van Dijk. Then, we try to describe the situation for each type of access by using both available knowledge and empirical findings. In the conclusion, we point out evidence of the digital divide in the Czech Republic and to weaknesses requiring further research.

2. Data and Methodology

Where available, information was obtained from the data of the Czech version of the World Internet Project. The World Internet Project (WIP) is a worldwide project based on a longitudinal study examining the influence of computers, the Internet and related technologies on the individual, family and society. The project has been coordinated by the Center for the Digital Future at USC Annenberg (http://www.digitalcenter.org/) in the USA. The first survey was carried out in 1999 in the USA, and by now, over 20 countries have joined the project. Each of them is responsible for the administration and funding of an annual quantitative survey. In the case of the Czech Republic, the funding is provided by the Ministry of Education and the project is entitled “World Internet Project – Czech Republic” (1P05ME751) and has been organized by the Faculty of Social Studies of Masaryk University in Brno.4

Most of the data processed in our analysis comes from the third annual questionnaire survey representing the population of the Czech Republic over 12 years old. We use the data from the year 2007 (N=1582) and for presenting the time series, we refer to the data collected in the years 2005 (N=1832) and 2006 (N=1705).5 This data source will be indicated as WIP CZ in the following text.

Because WIP CZ was not primarily designed with the goal of mapping the various dimensions of the digital divide in mind, some parts of the model were not examined. To fill the gaps in a model, we will use the information published by the Czech Statistical Office (CZSO) 6 , and the publicly available results from the Research of Information Literacy that was commissioned in 2005 by the Ministry of Informatics of the Czech Republic.7

3. A Model of Successive Kinds of Access

Van Dijk’s argument is based on developing ‘the core argument’ into a model of four successive kinds of access.

The core argument can be lucidly depicted as a causal model:

As we can see, the core argument ‘begins’ with stating the existence of socially maintained mechanisms of unequal distribution of resources. This distribution can be understood as the function of culturally and historically conditioned personal (e.g., young-old, male-female, white-black, and introvert-extrovert) and positional (employed-unemployed, employer-worker, parent-child, city-rural area, and high education-low education) categorical inequalities.8 The consequent distribution of resources then causes different access to ICTs. As ICTs are becoming the crucial means of participation in various spheres of social life (labor market, social relationships, education, culture, politics,… ), different access to ICTs is then reinforcing categorical inequalities, therefore contributing to increasingly unequal distribution of resources (van Dijk, 2005, p. 15). The importance of different access to ICTs as the new source of inequality is granted by the proceeding informationalization9 of the respective spheres of society and by the increasing role of ICTs in sustaining and creating social networks (ibid., pp. 131-162). The conclusion of the book is that “those at the ‘wrong’ end of the digital divide will become second-class or third-class citizens, or no citizens at all.” (ibid., p. 17)

Van Dijk uses the term ‘wrong end’ because of the stress he puts on multidimensionality of ICT access and the continuity between heavy users and the truly unconnected. To provide the growing body of ICT access research with a theoretical framework, van Dijk constructed the above-mentioned model of four successive stages of access to ICTs: motivational, material, skills and usage access. The word ‘successive’ is important here because the use of respective technology (for example the Internet) on every subsequent stage is conditioned by having minimal access at the lower level; for example, obtaining material access does not imply usage access without having motivation and appropriate skills. The proposed model van Dijk depicts as follows:

In the next chapter, we will describe the state of the digital divide in the Czech Republic by providing a model with available data. In the case of missing data, we will present basic findings from respectively aimed research performed abroad (mostly from the US where ICT access research has a strong tradition; however, socioeconomic differences have to be taken into consideration). In some cases, development in the Czech Republic and in other countries will be compared to support the argument.10

4. Applied Model: The Digital Divide in the Czech Republic

4.1. Material Access 11

Before we concentrate on the situation across various social groups, let us outline the general overview of Internet use in the Czech Republic in 2007. In this year, 55% of the population older than 12 years used the Internet. The average age of an Internet user was 33 years old as opposed to the average age 53 years old in the group of nonusers. Regarding the net monthly income of household, the largest share of users earned between 25,000 and 35,000 CZK, while it was between 15,000 and 25,000 CZK in the case of nonusers.

Five factors were processed to see the dynamics of material access: gender, age, social status, education and net monthly income. We have constructed tables based on the data obtained in 2005, 2006 and 2007 from the WIP surveys. The output is summarized in Fig. 3. In the following lines, we are going to focus on two things: the differences between observed groups and the dynamics of Internet penetration in the respective groups.

As far as age is concerned, the trend is quite clear—the probability of using the Internet declines with increasing age. The age groups up to 48 years old were above the national average of 55% of Internet users. However, the asymmetry in physical access between the most and the least connected age group was enormous: 93% to only 12%. Looking at the rates of growth, the only stagnating groups were 34-40 and 55+. The highest pace of growth was in the age group 19-33 (we can assume that the age group 12-18 is growing slower because it is already approaching the level of saturation).

A slight difference of 8% persists between men and women across the samples. The WIP CZ results are confirmed by the CZSO findings; whereas in 2003 the Internet was used by 30.8% of men and 25.3% of women older than 16, the difference was 48.8% and 41.5% in the year 2007 (CZSO, 2007). This result is interesting because in most economically developed countries the gender is one of the few characteristics for which the divide in physical access is steadily narrowing or already closed (Fallows, 2005; USC Annenberg School Center for the Digital Future, 2004, p. 31; van Dijk, 2005, pp. 59-60). It seems that the gender divide has remained almost the same over the past five years in the Czech Republic. However, the difference is negligible compared to other measured sociodemographic characteristics.

Regarding the social status, we can claim that students, self-employed and businesspersons form the most connected groups, being far above the national level. The unemployed and notably the retired are lagging behind significantly. Concerning the rate of growth, most of the groups have experienced app. 6% growth, except for retired people that copy the stagnation observed in the oldest age group.

Source: WIP CZ, 2005, 2006, 2007 (All respondents)

We can see that the Internet penetration in the overlapping groups of students and teenagers is probably near its absolute peak (the Internet can hardly be adopted by everyone in a given age group). We assume that such a high penetration in these groups reflects in the first place governmental support of connecting the schools to the Internet (governmental project ‘Internet for Schools’). In the second place, it reflects the equally important role of technological gadgets in the contemporary subculture of youth (cf. Castells, Fernández-Árdevol, Qiu, & Sey, 2007, pp. 127-169; Campbell & Park, 2008, pp. 379-380), and the network effect of Internet use in this subculture12.

Looking at the significance of the attained level of education, 13 several things deserve our attention. Firstly, the share of Internet users is growing at almost the same rate in all education groups. On the contrary, those without “Maturita”—which is the Czech equivalent of British GCSE or French baccalaureate—are substantially less likely to use the Internet.

The same small rates of growth can be observed in different income groups with the exception of those with an income in the range of 15,000 to 25,000 CZK, where a steep decline occurred. 14 This group does not reach the national level of physical access to the Internet.

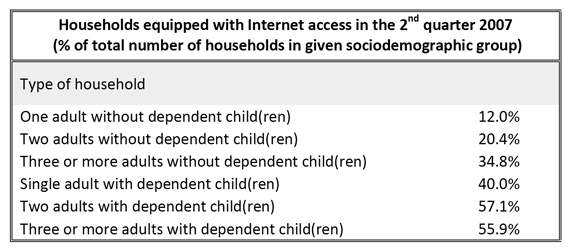

As for factors not shown in the table 1, size of household and having (school-going) children play an important role in being connected to the Internet. Van Dijk (2005, p. 56) emphasizes that this (often neglected) factor is “perhaps the most important driver in trying to get physical access”. The shares of respective types of households can be seen in the following table:

Source: CZSO, 2007

Therefore, it is not an overestimation to say that there is a quite serious divide in physical access in the Czech Republic. From the five examined sources of categorical inequalities, four were found to play an important role in probability of being connected to the Internet. The probability that the Internet is used by elder, less educated people from low-income households with fewer members is inconsiderable in comparison with the young generation, people with higher education, businesspersons, living in a higher-income household, or in a household with dependent children. 15

The problem is that this particular divide is far from being closed; as is indicated in the WIP CZ data; physical access divide is not narrowing but widening in the Czech Republic. Comparison with the data reported by the CZSO proves this to be true: whereas the share of users in the age group 16-24 increased from 59.5% to 80% between 2003 and 2007, the change was only from 1.5% to 4.4% (!) in the age group 65+ during the same period (CZSO, 2007). This would not be such a serious problem without the existence of a strong push towards digitization that permeates all important spheres of social life and participation—education, e-government efforts, electronic booking, the health care system, the labor market, the mass media system, social relations, etc. Under such conditions, those without access could really become ‘second’ or ‘third’ class citizens…, or is it already happening?

4.2. Motivational Access

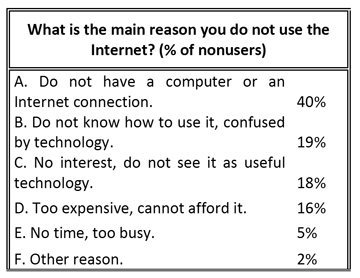

WIP CZ 2007 also contained the question about the main reason why a nonuser respondent does not use the Internet. The most frequently stated reason was “I do not have a computer or an Internet connection”; 16% of respondents rejected going online because it is too expensive. Therefore, it seems like the biggest problem of connecting two thirds of contemporary nonusers is the lack of material access (partially solvable by the availability of a place where one could connect to the Internet for free or at least cheaply). One in five respondents did not see the internet as useful technology or were not interested at all. Almost the same share admitted lack of skills (see subchapter 4.3.). Lack of time was the main reason for only 5% of nonusers. 16

Source: WIP CZ, 2007, N=713 (Nonusers)

We do not agree with van Dijk that having no interest in using the Internet means just ignorance or a misunderstanding of the benefits of using the technology in question (cf. van Dijk, 2005, p. 43). We claim that the absolute substitution of other means of communication with the Internet is not possible; simply said, there are still social groups for which the use of the Internet is not very beneficial compared to the use of other available—and less resource-demanding—means of communication (e.g., face-to-face, mobile phones). 17 If we accept the view that the nonusers stating A, B, or D as their main reason would use the Internet after solving their main problem, there remains about one fifth of nonusers who simply do not want to and probably also do not need to be connected. Nevertheless, here we are leaping to what should be the conclusion of such an analysis—the proposal of policies needed to solve the divide problem. And it would be pointless without understanding the crucial stage of access: skills access.

4.3. Skills Access

Many terms have been used to grasp the ability to use hardware and software for one’s own purposes: computer literacy, information literacy, digital literacy, media literacy, information capital, computer skills, and so on (van Dijk, 2005, pp. 71-73). Van Dijk recognizes three dimensions of skills access that can be understood as the successive stages within the general concept of digital skills18. According to van Dijk’s definition (ibid., pp. 73-74, emphasized by van Dijk),

Operational (and partly information) skills have been the centre of attention of researchers because they are relatively easy to measure. As can be inferred from its definition, the strategic skills level is essential for stating the digital divide as a social problem requiring political intervention. Only strategic skills connect the ownership of ICT and other digital skills with such ICT use that improves one’s position in certain spheres of social life or at least helps to spare (mostly temporal or material) shortage resources. The problem is that the research has almost exclusively neglected this type of skills until now. Although being aware of this problem, van Dijk devotes only two more or less theoretical pages to the strategic skills chapter, while offering no clear example (ibid., pp. 88-90). Generally, strategic skills represent the ability to employ a wide range of heterogeneous resources (knowledge, money, power, social networks, laws, traditions, technologies, etc.) to reach a particular goal in an efficient way. In the case of van Dijk’s model, using ICT devices (1) to create, maintain, mobilize and dynamically utilize one’s own social network, and (2) to search, process, and evaluate quickly needed information should represent an important competitive advantage in comparison to “not digitized” strategies using less flexible and more resources demanding means of communication, information processing, and mobilization of resources. Unfortunately, for the reason that the research has neglected the strategic skills topic, there is almost no empirical evidence of the relation between Internet use and participation in society. As a substitution, van Dijk grounds the digital divide as a political problem on the thesis of emergence of information/network society in which ICT access becomes the crucial precondition of social participation (ibid., pp. 131-161). We think that proofing ICT use as beneficiary and the digital divide as an emerging problem in society does not necessarily mean a nationwide urgency for everyone to be skillfully using the Internet at an expert level. The reason is that Internet use has different ‘added value’ for different users and therefore the relevance of the digital divide problem is different in various social contexts. Relating this proposition to the general strategic skills concept as it was mentioned above, we propose distinguishing two basic types of nonusers according to their ability to take advantage of ICT by delegating its use to another person or social network. 19 This distinction is yet waiting to be conceptualized and empirically discovered.

In the Czech Republic, probably the best source of information about the distribution of operational and informational skills has been the above-mentioned Research of Information Literacy. Six areas of information literacy were examined: awareness of IT wording, computer handling, word processor handling, spreadsheet handling, graphics handling, and internet handling20. Respondents could score in each area on three capability levels: basic, medium, and upper. Information literate respondents had to be able to reach at least the basic capability level in all factors (MICR & STEM/MARK, 2006). As we can see, the research was almost exclusively focused on operational skills (this is usual in a similar type of ICT literacy research because of the difficulties that measuring informational and strategic skills represents); furthermore, Internet handling factor represented only one sixth of the final score.

The results are very interesting from the perspective of the skills divide. The share of information literates in the population was 21% after verification with real tasks21; computer literacy was declining with increasing age—there was for example 52% of information literate in the age group 15-17, but only 2% in the age group 61+. Women were identified as having much lower level of operational skills than men (in fact, women scored quite well in word processor handling and computer handling but lagged behind in other items). Several types of users were constructed on the base of the information literacy score. From the perspective of this article’s task, the demographic characteristics of these types are very interesting. For example, the type ‘surfer’ (upper level or almost upper level in all information literacy components) was represented by 84% of men in contrast to only 16% of women; 45% of ‘surfers’ had a secondary level of education as compared to 16% of those with a university degree; and, not surprisingly, 53% of ‘surfers’ were from the age group 18-28. (MICR & STEM/MARK, 2005)

Similar results have been provided by CZSO (2007). 22 In the year 2007, 30.9% of men were identified as having high level of internet skills in contrast to 14.4% of women in the same category. Concerning the age, it was 35.8% in the age group 15-24 in contrast to 12.4% in the age group 55-64.

Comparison of these skills asymmetries with the physical access data then leads to a completely different picture of the gender digital divide, which seems to be functioning on the level of skills differences rather than on the level of material access. Besides gender, the distribution of operational (and partly even informational) skills in the group of users almost copied the distribution of material access in the whole population therefore implying the dimension of depth in the digital divide. In other words, the inequality stemming from the distribution of material access is amplified by a similarly uneven distribution of skills access within the population of users; this means that the digital divide is working simultaneously on more levels of access.

The problem with getting a notion of strategic skills in the Czech Republic is that almost all relevant indicators in available research are indirect (i.e., are in the form of subjective evaluation of the benefits of Internet use in provided areas). To outline the impact of Internet use on the participation in the spheres of work and social relations, we chose three indirect indicators: change in work efficiency, change in social contact, and number of offline/online social ties. These indicators refer to the higher amount of resources that can be mobilized when needed to maintain or increase participation in respective spheres of social life. They also refer to better participation in the related spheres of social life (labor market, social relationships).

As for the change in work efficiency, 54% of Internet users replied23 that their work performance/productivity had improved due to Internet access, whereas only 1% replied that their productivity/performance worsened for the same reason (40% of users stated that their productivity/performance remained the same).

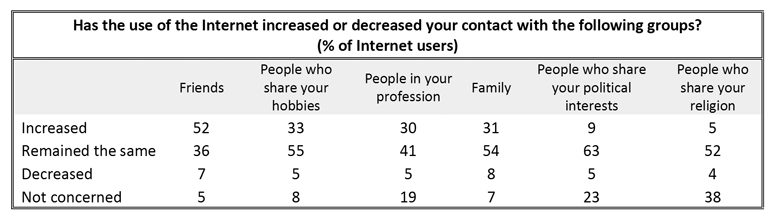

The question focused on the change of contact with selected groups24 showed that according to users, Internet use significantly increases social contact. More than half of users declared that Internet use increased their contact with friends; increase was also declared by one third of users in cases of family and people sharing the same profession or interests. Detailed results can be seen in table 4.

Source: WIP CZ, 2007, N=869 (Internet users)

Another set of questions, dealing with sociability effects of Internet use, aimed at the number of online friends and the number of online friends that turned to be off-line friends. Forty percent of Internet users had at least one online friend they had not met personally; one quarter of Internet users had at least five such online friends. Almost one quarter of Internet users had at least one ‘offline friend’ whom they had met originally on the Internet. From those having at least one online friend they have not met personally (N=344), 72% claimed that at least one of them was a close friend. It seems that both age and gender have no effect on having online friends; data reflect only the bigger popularity of communication applications among young people. However, offline sociability matters in this case; WIP CZ 2007 data shows that the more offline friends one has, the higher the probability of having a higher number of online friends is25. Findings obtained during analysis of these data seem to support the thesis that Internet use increases social capital (Castells, 2001, pp. 116-146; Ellison, Lampe & Steinfield, 2007; Qan-Hase & Wellman, 2002; Molnár, 2004; USC Annenberg School Center for the Digital Future, 2007). Regarding the benefits of Internet use, experience abroad shows that the Internet becomes an important part of decision-making in life’s important moments and that the share of people benefiting from Internet use in this way grows over time (Horrigan & Rainie, 2006).

The problem is that stating the benefits of Internet use in these areas does not sufficiently prove a higher participation in society in general (and thereby the fact of being connected as a partly independent contribution to social inequality). As far as skills access is concerned, future research should aim at proving the relation between specific ways of Internet use (or delegation of Internet related tasks) and the level of social participation. Special attention should be paid to the ways people are disadvantaged because of being disconnected. Another challenge is to recognize the variations of types of strategies (to increase one’s participation) employed by people from different social strata and by various types of users.

An important part of skills access that was not yet mentioned should be remarked before moving to usage access: the ways users acquire digital skills. Van Dijk emphasizes that two of the most important sources of learning are trial-and-error learning and the assistance of people close to the user (i.e., friends, colleagues, children, and parents), not training courses or classes. Findings from CZSO (2007) support this claim; the most frequently mentioned way of obtaining the computer skills were informal assistance from friends, colleagues, etc. (68%); self-study in the sense of learning by doing (57%); and self-study using books or CD-ROMs (40%). Moreover, there were no big differences according to age, gender, education, social status or type of locality.

4.4. Usage Access

Usage access is the final stage representing the use of specific media for one’s purposes. The actual way of using certain technology (in this case, the Internet) is conditioned by the previous stages of access: specific motivations and goals, accessible technology, the context of its use, and skills. However, preceding stages do not determine usage access; it has its own logic.

We can observe three basic sources of the digital divide at the level of usage access: (1) amount of usage time, (2) usage diversity and the type of preferred online activities, and (3) the properties of used technology (van Dijk, 2005, p. 107-116).

None of the sources we have studies surveyed the exact time spent on using the Internet. For this reason, we have to refer to information obtained in other countries in this case (we legitimately assume that the situation in the Czech Republic will be similar to other countries as in the case of other stages of access). Comparing the development of the time spent on using the Internet across various social groups in the United States and in the Netherlands, van Dijk concludes that the usage divide has been progressively widening in these countries (ibid., pp. 107-110). Because the time spent on using the computer is related to the level of respective digital skills (as we have seen in previous subchapter), the combination of skills divide and usage gap represents the most troublesome part of the polarization of users (ibid., pp. 125-126). The typical usage pattern of the experienced user as compared to newcomers and occasional users is a longer time spent online, a bigger diversity of applications and functions used, a preference for a higher-speed connection, and different online activities preferred.

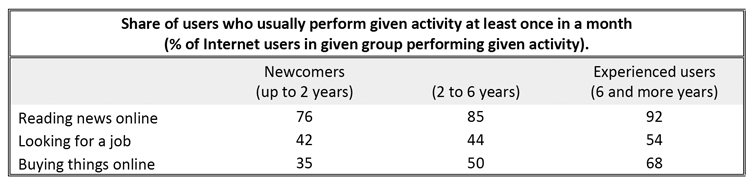

Inspired by findings from the Center for the Digital Future (UCLA, 2003), we have decided to look closer at the difference between new and experienced users in terms of performing three representative activities (table 5). We have divided the total number of users (N=867) into three groups according to the years of Internet use: (A) new users (up to two years); (B) those with two to six years of experience; and (C) experienced users (six or more years of online experience). According to WIP CZ 2007, the first group equaled 12.5% of Internet users, the second equaled 57.1% and the last, 30.4%.

Source: WIP CZ, 2007, N=869 (Internet users)

Concerning reading news, we can say that it is a widespread activity. However, the share of ‘readers’ increases with the years of experience. According to UCLA studies, the experienced users tend to consider the Internet as their main source of news and information (e.g., UCLA, 2003, p. 35). This is also related to the fact that experienced users tend to spend less time watching TV than other groups (ibid., p. 34). Quite the opposite can be found as regards the job-hunting activity. There is in fact no greater difference between the newcomers and those with 2 to 6 years of experience (social status and age seem to be the only characteristics influencing the time spent on job-hunting on the Internet). As for buying things online, we can observe quite a big difference between the newcomers and experienced—35% to 68%. Again, this is in line with the findings of UCLA studies where experienced users are more likely to trust online money transactions (ibid., p. 19). The strength of the factor of user experience is very important because it allows the development of skills and usage patterns relatively independently of the sociodemographic profile of the respective users. Therefore, even those at the ‘wrong-side’ of the digital divide can catch up with the information elite under the preconditions of being motivated, having material access and learning support in the community, and possessing enough time to develop the skills.

Again, we have to emphasize the importance of primary relations for obtaining access at all levels. As van Dijk (2005, p. 122) points out, “the larger the household and the more (school-going) children it has, the more computers and Internet connections actually are used, the longer users use the computers, and the more different applications are used. This is not only a matter of adding individuals but of a mutual exchange of ideas, interests, and experiences among members of the household.” The problem is that traditional personal characteristics which the digital divide research has been focused on (age, income, gender, ethnicity, and so on) are not suitable for understanding the meaning of positions and relations of individuals in their social networks (household, work, class, interest group, and so on). 26 The importance of relational characteristics should be kept in mind when one tries to understand the logic of digital divide development and to propose counter-digital divide precautions and remedies. Broadening the scope to relational characteristics of respondents weakens the importance of personal characteristics significantly, which have been favored in digital divide research. As in other countries, the ICT access research in the Czech Republic has also paid insufficient attention to this relational aspekt. 27

To make a puzzle complete, the last major factor severely afflicting the chances of the disconnected and newcomers to catch up with experienced hardwired users must be mentioned: a technological innovation.

4.5. Innovating the Digital Divide: The Broadband Issue

The technology in question is very complex and changes very quickly therefore making the equipment (and related skills) quickly obsolete. One of the basic difficulties any policy trying to deal with the digital divide issue must face is the perpetual innovation. For example, in the time the unconnected population started catching up with skilled users by getting a modem connection, experienced users escaped to the higher level of Internet use by getting broadband connection. It allowed them to use a vast amount of new functions and applications continuously, without the need to get disconnected from the Internet after finishing a particular task. This ‘new technological divide’ (Castells, 2001, pp. 256-257) represented one of the main counter-arguments in the years since the digital divide closure was proclaimed. Let us look briefly at the divide that emerged between those connected by slow dial-up technology and those connected by a high-speed Internet connection. In van Dijk’s model, every innovation brings users back to the stage of motivational access to decide whether they catch up or technologically lag behind.

According to WIP CZ, 67% of Internet users older than 12 years claimed to be connected via broadband from home in 2007; according to CZSO, it was 26% of households28 representing 80% of all households connected. The characteristics of broadband adoption copy the prior development of the sociodemographic structure of dial-up users (CZSO, 2007; supported also by WIP CZ data). As for those still using narrowband connection, CZSO surveyed the motivations of not switching from narrowband to broadband. The top mentioned reason in 2007 was ‘no need’, which was claimed by 42% of narrowband users. 29 As in the case of Internet access motivation, the question is whether this ‘no need’ is just misunderstanding of the broadband connection merits or whether it really reflects such type of use for which dial-up is sufficient. According to Horrigan and Rainie (2002) and Horrigan (2006), broadband users develop different skills and use the Internet in a different way than dial-up users: they post more content on the Internet, they use the ‘always on’ feature to do significantly more information queries, and the spectrum of their online activities is much wider.

Still, emerging technologies of both software applications and connection speed promise another differentiation of Internet use therefore further deepening the digital divide as we know it today. Van Dijk warns against a laissez faire approach, which might solidify the digital divide as the new durable inequality dividing population according to ICT use (van Dijk, 2005, pp. 66-69). Yet, some important questions wait to be answered to realize what we face.

5. Conclusion

A big challenge for sociology is to grasp the digital divide issue in its complexity without losing the ability to propose efficient steps to improve the situation.

According to the WIP CZ findings shown above, we assume that about four-fifths of nonusers are potential Internet users. The basic problems are lack of public access points or awareness of them, lack of digital skills, and low understanding of what is Internet use good for and what are its main assets.

The sociodemographic distribution of physical access and its development shows that big parts of Czech society are seriously lagging behind the informationalization process; it counts especially for the older generation, people with low education, people from low-income households, and people having insufficient social contact with people who might be more likely connected. Moreover, this gap has been widening up to the present time.

According to data, there seems to be no serious gender divide in terms of physical access; however, women are significantly lagging behind when we look at the differences in respective digital skills. Besides gender, the sociodemographic distribution of skills among users seems to copy the distribution of physical access, making the digital divide deeper than might be expected only from the Internet penetration data. Being a crucial point in the reasoning, skills access requires further research aimed at two main goals. Firstly, strategies of efficient learning should avoid repeating the mistake of formal computer courses focused primarily on basic operational skills in the context of individual learning. Instead, they should take into consideration the importance of learning by doing in the context of small informal groups. Motivation must be prior to learning operations and both of them are not a sufficient precondition of efficient ICT use without the framework of understanding personal Internet use benefits (whichever they might be). Secondly, the elaboration of strategic skills is required by means of qualitative research in the first stage. We stress understanding of the situation prior to quantitatively aimed analyses because the digital divide research seems to be spoiled by the theoretical background of the information society concept that does not seem to reflect all facets of the complexity of the digital divide problem. The situation is changing every year but we do not see enough evidence for claiming everyone should be connected without granting the benefits of Internet use. Only when we understand in what sociotechnological contexts Internet access represents a competitive advantage, can we firmly defend the digital divide as a problem that should be treated politically.

On the level of usage access, publicly accessible data about the exact time spent on using the Internet are missing and the elaboration of types of usage practices would be contributive to understanding the state of the usage divide. We also stress the importance of strategic skills development that should respect the specific needs of individuals. We believe that if research confirms the urgency of ‘shallowing’ the digital divide then the policies aimed at skills divide will become essential.

Finally yet importantly, digital divide research should turn away from obsession with the Internet use as the only way to participate in the information/network society; the media environment is quickly changing and people use various means to satisfy their communication and participation needs. We have emphasized the role of mobile phones that have reached an almost absolute level of penetration in all sociodemographic groups, opening the question of the substitution of Internet access for mobile-phone social networking and social capital.

We have found persuasive evidence of the digital divide deepening in the Czech Republic. In spite of all conceptual problems, findings obtained from the data do not allow us to refute the concept of the social importance of equal Internet access. We hope that the digital divide challenge will not remain untreated in the Czech Republic and that future research will provide useful information to reverse the unpleasant trend we are witnessing.

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowledge the support of the Czech Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (MSM0021622406 and 1P05ME751).

References

Anderson, J. Q. (2005). Imagining the Internet: Personalities, predictions, perspectives. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Brown, R., & Gore, A. (1996). The Global Information Infrastructure: Agenda for cooperation. DIANE Publishing.

Bucy, E. P., & Newhagen, J. E. (2004). Routes to media access. In E. P. Bucy & J. E. Newhagen (Eds.), Media access: Social and psychological dimensions of new technology use (pp. 3-23). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Campbell, S. W., & Park, Y., J. (2008). Social Implications of Mobile Telephony: The Rise of Personal Communication Society. Sociology Compass, 2, 371-387.

Castells, M. (1996). The Information Age: Economy, society and culture; Volume I: The rise of the network society. Oxford: Blackwell.

Castells, M. (2001). The Internet galaxy: Reflections on the Internet, business, and society. New York: Oxford University Press.

Castells, M., Fernández-Árdevol, M., Qiu, J. L., & Sey, A. (2007). Mobile communication and society: A global perspective. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Czech Statistical Office (CZSO). (2005). Results of ICT Usage Survey in Czech Households and among Individuals 2005. Retrieved January 27, 2008, from http://www.czso.cz/csu/2005edicniplan.nsf/engp/9603-05

Czech Statistical Office (CZSO). (2007). Use of ICT by Households and Individuals in 2007. Retrieved January 27, 2008, from http://www.czso.cz/csu/2007edicniplan.nsf/engp/9701-07

Ellison, N. B., Lampe, C., & Steinfield, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook "friends:" Social capital and college students' use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4). Retrieved from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol12/issue4/ellison.html

Fallows, D. (2005). How women and men use the Internet. Washington, DC: Pew Internet and American Life Project. Retrieved November 25, 2007, from http://www.pewinternet.org/PPF/r/171/report_display.asp

Gordo, B. (2003). Overcoming digital deprivation. IT&Society, 1, 166-180.

Gore, A. (1993). Remarks by Vice President Al Gore at National Press Club, December 21, 1993. Retrieved November 21, 2007, from http://www.ibiblio.org/nii/goremarks.html

Hacker, K. L., & Mason, S. M. (2003). Applying communication theory to digital divide research. IT&Society, 1, 40-55.

Horrigan, J. B. (2006) Home Broadband Adoption and Online Content Creation. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved February 8, 2008, from http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_Broadband_trends2006.pdf

Horrigan, J. B., & Rainie, L. (2002). The broadband difference: How online Americans' behavior changes with high-speed Internet connections at home. Washington DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved January 25, 2008, from http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_Broadband_Report.pdf

Horrigan, J. B., & Rainie, L. (2006). The Internet’s growing role in life’s major moments. Washington DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved November 18, 2007, from http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_Major%20Moments_2006.pdf

Katz, M. L., & Shapiro, C. (1994). Systems Competition and Network Effects. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8, 93-115.

National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA). (1995). Falling through the Net: A survey of the "have nots" in rural and urban America. Retrieved November 15, 2007, from http://www.ntia.doc.gov/ntiahome/fallingthru.html

National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA). (1999). Falling through the Net: Defining digital divide. Retrieved November 15, 2007, from from http://www.ntia.doc.gov/ntiahome/fttn99/

National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA). (2002). A nation online: How Americans are expanding their use of the Internet. Retrieved November 15, 2007, from http://www.ntia.doc.gov/ntiahome/dn/nationonline_020502.htm

Ministry of Informatics of the Czech Republic & STEM/MARK (MICR & STEM/MARK). (2005). Výzkum informační gramotnosti; Prezentace hlavních výsledků výzkumu [PowerPoint Slides]. Presentation of the main findings from the research at the press conference in Hilton Prague, August 25, 2005. Retrieved January 20, 2007, from http://www.policie.cz/micr/images/dokumenty/prezentace_vyzkumig.ppt

Ministry of Informatics of the Czech Republic & STEM/MARK (MICR & STEM/MARK). (2006). Information literacy in a nutshell; ... Market research. Research Report. Retrieved January 25, 2008, from http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/16/5/36988619.pdf

Molnár, S. (2004). Sociability and the Internet. Review of Sociology, 10, 67-84. Retrieved from http://www.ittk.hu/english/publications.html

Quan-Hase, A., & Wellman, B. (with Witte, J. C., & Hampton, K.). (2002) Capitalizing on the Net: Social contact, civic engagement, and sense of community. In B. Wellman & C. Haythornthwaite (Eds.), The Internet in everyday life (pp. 291- 324). Oxford: Blackwell.

Text of President Clinton's 1998 State of the Union Address, Congressional Record. (1998, January 27). The Washington Post. Retrieved January 28, 2007, from http://www.washingtonpost.com

Tilly, Ch. (1998). Durable inequality. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

University of California, Los Angeles, Center for Communication Policy (UCLA). (2003). The UCLA Internet report 2003: Surveying the Digital Future, Year three. Los Angeles: Author. Retrieved January 23, 2008, from http://www.digitalcenter.org/pdf/InternetReportYearThree.pdf

USC Annenberg School Center for the Digital Future. (2004). The digital future report: Surveying the digital future, year four; Ten years, ten trends. Los Angeles: Author. Retrieved January 30, 2008, from http://www.digitalcenter.org/downloads/DigitalFutureReport-Year4- 2004.pdf

USC Annenberg School Center for the Digital Future. (2007). Online world as important to Internet users as real world? Los Angeles: Author. Retrieved January 30, 2008, from www.digitalcenter.org/pdf/2007- Digital-Future-Report-Press-Release-112906.pdf

van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2005). Deepening digital divide: Inequality in the information society. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2006a). Digital divide research, achievements, and shortcomings. In Poetics, Vol. 34, Issues 4-5, pp. 221-235.

van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2006b). The network society: Social aspects of new media (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

(1) Argument here is based on the criticism of the basic S-curve of the adoption of innovation; for more details about the logic of this criticism, see van Dijk (2005, pp. 61-65) or Hacker & Mason (2003, pp. 45-47).

(2) We will present the weaker parts of the model later in the text .

(3) The discursive limits of information society debate and its role in politics of digitization are still waiting to be elaborated.

(4) The person in charge of the project is PhDr. et Mgr. David Šmahel, Ph.D. (http://www.terapie.cz/smahelen). Further information about the World Internet Project can be found at (http://www.worldinternetproject.net/).

(5) The data were processed in SPSS software. If not indicated otherwise, the results summarized in the tables are at 95% confidence .

(6) For the detailed information about the methodology used by the Czech Statistical Office in respective surveys, see its webpage at (http://www.czso.cz) or at (http://www.oecd.org/sti/ictmetadata). The CZSO’s sample is 16+. One of the basic differences that should be mentioned here is the definition of Internet user; whereas the WIP CZ defines the user as the one who replies positively to the question ‚Do you personally use the Internet?‘, CZSO use the question ‚Did you use the Internet in the last 3 months?‘ Different definitions are the reasons why the shares of Internet users in population differed between the two measurements.

(7) The data for this research were gathered in three waves from 15 000 respondents (18-60 years; another two 500 respondents samples were gathered for age groups 15-17 and 60+) by CATI method. On the base of the results from this phase of the research, several in-hall tests were performed to verify the self-reported information literacy. For more information about the research, see MICR & STEM/MARK (2006), or contact STEM/MARK marketing research agency at www.stemmark.cz .

(8) Van Dijk uses Tilly’s concept of categorical inequalities in his theory; see Tilly (1998, pp. 6-9) .

(9) The neologism ‘informationalization’ refers to the process of social transformation towards the society that more or less fits the definition of the information(al) society, i.e, society where ICTs permeate and affect all spheres of human activity. Therefore, the ‘informationalized society’ is a theoretical category referring to such a society where ICTs are already enrooted in major spheres of human activity.

(10) We would like to emphasize that even if van Dijk’s theoretical framework refers to ICTs, the parts of research results we will be using in this article will be about technology that is generally understood as the embodiment of the term ‘ICT’: the Internet. We are aware of the weakness of not including other ICTs (e.g., mobile phones) and their interaction with Internet use into the model, but this has been the heritage of the digital divide research design from the nineties when the necessary information about the digital divide was obtained from Internet penetration (i.e. material access) research. This logic is still waiting to be overcome in future research focused on the digital divide problem as such.

(11) The reason for introducing material access before motivational access is that we want to show first the overall situation of Internet diffusion in the Czech Republic .

(12) The network effect has been used mostly in IT economics and refers to the observation that “the demand for a network good is a function of both its price, and the expected size of the network.” (Katz & Shapiro, 1994, p. 96). In the case of ICT use, it means that the higher share of people in a group use ICTs, the higher value ICT use has for all members of the group. Concurrently, as the share of ICT users in the group increases, nonusers start to be partly excluded from the social life of the group. We refer to the network effect in the second place because of the lack of empirical evidence that the Internet is the most important communication tool of the Czech teenagers (we hypothesize that mobile communication exceeds the Internet in this respect) .

(13) Students were not accounted here so we can see the ‘real’ penetration of those with attained primary and secondary education .

(14) We think that this decline could be caused by the fact that a relatively large number of respondents (about one quarter in this case) refuse to answer the household income question in the Czech Republic therefore skewing the results.

(15) Among other disadvantaged groups that are not mentioned in this article are the disabled, ethnical minorities, and people living in less densely populated areas. For more details about their Internet use, see CZSO (2007).

(16) On the contrary, Internet users claimed the lack of time to be the biggest obstacle to use the Internet more intensively. As CZSO survey (2007) revealed, 65% of Internet users had this opinion. One quarter of users claims that the cost of connection is too high, ranking as the second most frequent reason. In sum, roughly 30% of users wish to use the Internet more intensively (ibid.).

(17) An example can be elder people using mobile phones .

(18) Whereas skills access is a general category, digital skills are the type of skills relevant for the use of ICTs. This specification is important because van Dijk claims the successive model to be applicable to any medium (van Dijk, 2006b, p. 178). In addition, we are convinced that its use can be extended to any technology. It can be for example used to analyze ‘car divide’ in a society where the possession of and ability to drive a car represents an important means of participation in the various spheres of social life (the example might be found in the United States). Then, the type of skills needed would be naturally different from those necessary to operate and efficiently use a computer.

(19) In the first group, there would be socially skilled people with no or low digital skills (they can be managers, parents, wives, and so on). The problematic nonusers are then those who do not have the digital skills and have a small probability of delegating the ICT-related tasks.

(20) The basic level of Internet handling was operationalized as an ability to discover the URL, search for information, fill a web form, write a simple email, and send a file via email (MICR & STEM/MARK, 2006).

(21) It was 23% before verification by in hall tests; concerning the component of Internet handling, 34% of population were identified as having basic skills. According to CZSO (2005), there were 37.4% of users that have ever used the Internet in the population of 15+ in 2005.

(22) To define internet skills, CZSO use the methodology of OECD (see footnote 5).

(23) The change in work efficiency was measured by the question ‘because of your Internet access, do you feel that your work performance/productivity has improved a lot, improved somewhat, stayed the same, worsened somewhat, or worsened a lot?’

(24) ‘Has the use of the Internet increased or decreased your contact with the following groups? ‘ Offered groups were family, friends, people who share your hobbies, people who share your political interests, people who share your religion, and people in your profession .

(25) The Spearman correlation (0.282) is significant at the level α=0.01.

(26) There is an exception however in applications of the network approach in ICT social effects research (e.g., Barry Wellman).

(27) For example, both Information Literacy Research and CZSO did not publish computer/Internet skills distribution according to the type of household .

(28) This share grew rapidly; in 2003 it was only 2% of households, in 2005 it was already 15% of all households .

(29) One fifth of narrowband users claimed the broadband to be too expensive, 15% use broadband elsewhere and 12% are in the area where broadband connection is not available .