Creating Content or Creating Hype: Practices of Online Content Creation and Consumption in Estonia

Pille Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt1, Veronika Kalmus2, Pille Runnel32Institute of Journalism and Communication, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia

3Institute of Journalism and Communication, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia

& Estonian National Museum

Abstract

Key words: online content creation, digital media literacy, types of Internet use, Estonia

Introduction

Among Eastern European post-Socialist countries, Estonia has experienced one of the fastest political and economic transformations, which, in general, has been interpreted as a “success story” (see, e.g. Nørgaard 2000; Panagiotou 2001). A considerable part of that success is due to achievements in the field of the information society. The Lisbon Review (Blanke 2006) indicates that Estonia ranks as high as 5th among European countries in information society development. “In terms of the information society, its government is seen as successfully promoting the adoption of new information and communication technologies and is among the world’s best in terms of providing online government services. Estonian businesses also use these tools to a great extent in their business dealings, and a large number of individuals also use them (Estonia is ranked seventh in Europe in terms of Internet penetration)” (Blanke 2006: 6). Similarly, Estonia is ranked 27th by both Economist Intelligence Unit (2006) and Global Competitiveness Report (World Economic Forum 2007).

This accomplishment is also reflected in public rhetoric, where Estonia is often regarded as a leading e-state. Internationally and domestically recognized success (Kalvet 2007), mostly in the areas of e-governance and services, has generated expectations and hype in many people. It is, however, still debatable to what extent information society developments are rooted in micro-level practices and everyday uses of the Internet by individuals. The aim of this article is to look beyond the general statistics of Internet promotion and usage by asking what usage means in terms of fostering civic participation and democratic deliberation. We will particularly look at creative online practices, which are a critical part of digital media literacies.

In a contemporary informatising society, acquisition of media literacy is a part of socialisation. The processes of socialisation are changing in several crucial ways (Kalmus 2007a); also, literacies shift in response to social and cultural changes, as well as responding to the emergence of new technologies (Kellner & Share 2007). For instance, the Internet places an unprecedented amount of information on any topic in the hands of individuals who have access to it, and it also makes any computer user a potential “author of a new kind”, who can produce and publish texts, alter texts, write and “write back” (Kress 2003: 173). Due to new communication channels, such as various Internet forums, chat rooms, e-mail, text messaging, blogs, wikis and so on, (young) people may write more than ever before. Therefore, it is widely acknowledged that media literacy today involves the skills and knowledge to use media intelligently, that is, to discriminate and evaluate media content, as well as to produce texts and artefacts, and to construct alternative media (Kellner & Share 2007).

According to the skills-based approach, media literacy is the ability to access, analyse, evaluate and create messages in a variety of forms. Each component supports others as part of a non-linear, dynamic learning process: learning to create content helps one to analyse something produced professionally by others; skills in analysis and evaluation open the doors to new uses of the Internet, expand access, and so forth (Livingstone 2004). In order to be able to talk about the ways people are developing interpretative relationships with technologically mediated texts, Livingstone suggests going beyond the skills and talking about “literacies” in the plural rather than “literacy”. As the focus of this article is on Internet use, we shift from “media literacies” to “digital skills” and “digital literacies” in order to stress the specificity of using and creating digitally mediated content.

A number of online environments, such as wikis, multi-user online games, blogs, and so forth, actually break down the boundaries between producers and consumers and enable all participants to be users as well as producers of information and images. Bruns (2006) calls participants in these environments produsers and their activity produsage (production + usage) —“the collaborative and continuous building and extending of existing content in pursuit of further improvement” (p. 276). Within this context, he speaks of a new “Generation C”. The letter “C” stands, in the first instance, for “content creation” and, more generally, for “creativity” (Bruns 2005).

“Generation C”, however, is not ubiquitous. International research suggests that creative work of 12 to 18 year olds is limited: relatively few young people develop their own web sites or blogs, and these products can easily become dormant (MEDIAPPRO 2006; Kalmus 2007b).

Furthermore, previous studies have revealed crucial socio-demographic differences in young people’s creative online activities. For instance, Subrahmanyam (2007) argues that blogging appears to be a primarily female pastime, as the majority of 200 sampled English language weblog owners (aged 14 to 17 years) were female. Also, a survey among 11 to 18 year old pupils in Estonia revealed that girls tend to be engaged more frequently and in a greater variety of creative online activities than boys (Beljajev 2006). According to the same survey, younger pupils (aged 11 to 12) are most active in expressing themselves on the Internet (e.g. blogging, making their own websites etc.), while 17 to 18 year olds tend to be most passive.

Numerous previous analyses of representative population data (e.g. Kalmus 2006; Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt 2006; Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt et al. 2007) have also shown significant differences between socio-demographic groups (e.g. age, gender, educational and income groups) in various aspects of Internet use. Among those disparities, gaps between generations are most pronounced. Also, gender differences exist in a number of online activities, especially among the oldest age groups (see Kalmus 2006).

This article focuses on practices of online content creation and consumption among men and women, and among different age groups (with a special emphasis on younger age groups). We start our analysis by giving an overview of gender and age differences in general Internet use, as well as in regard to Internet user types. We proceed to an analysis of variation by gender and age in practices of online content creation and consumption. Finally, to view those activities in a wider context of Internet use, we analyse relationships between the types of Internet users and practices of online content creation and consumption.

Methods

This article is based on the representative population survey “Me. The World. The Media”, conducted in November 2005 in Estonia. The survey design was large-scale and complex, comprised of a self-administered written questionnaire and follow-up face-to-face interviews, with a total of approximately 800 variables, which covered the following areas: evaluation of societal changes and short-term history, political and social participation, values and identities, social space, use of foreign languages, life-style, consumption, cultural preferences, use of media, computers and the Internet, work and entrepreneurship, material resources, mobile phones and sustainable consumption.

A proportional model of the general population (by areas and urban/rural division) and multi-step probability random sampling was used. In addition, a quota was used to sample a proportional number of ethnic Estonians and Estonian Russians. The sampling was conducted at 150 survey points across Estonia, using the method of pre-determined starting address and route. To sample respondents in households, the rule of “the youngest male” was used (that is, the fieldworkers asked to speak with the youngest male member of the household; if he was not present, the youngest female was asked to participate etc.). The planned sample was 1500 respondents aged 15-74. The achieved sample was 1475 (51.3% of the addresses visited by the fieldworkers).

We operationalised practices of online content consumption and content creation in the form of the following eight activities: communicating in portals and reading commentaries; reading and commenting on blogs; downloading music; downloading movies; writing online commentaries; participating in forums; updating one’s blog or homepage; and uploading photos. The activities were measured on a five-point frequency scale (practically every day – a few times a week – a few times a month – a few times a year – never). For the clarity of data presentation, the frequency scale was reduced to three points: at least a few times a week – at least a few times a year – never.

To create a typology of Internet users, we reduced 46 variables describing various Internet usage practices to seven factors (by using principle axis factor analysis with Varimax rotation). Those factors were used as input data for two-step cluster analysis, which identified six Internet user clusters, which are listed from more active to more passive user type as follows: Versatile Internet user; Communication- and entertainment-oriented user; Pragmatic work and information user; Entertainment and family information user; Public and practical information user; Small-scale user. A more detailed description of the Internet user types can be found in Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt (2006) and Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt & Kalvet (2008, forthcoming).

Results

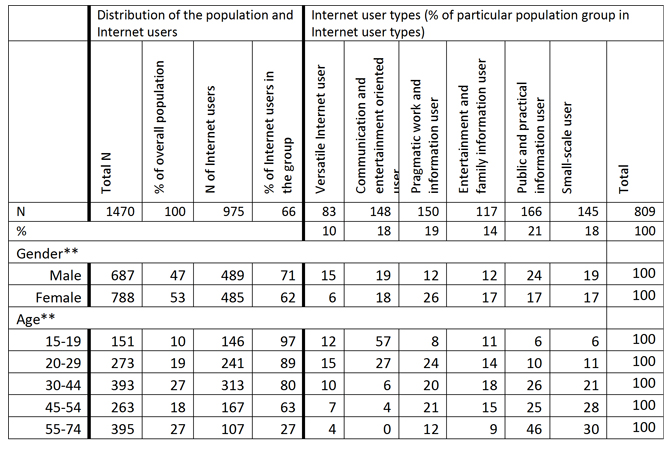

Table 1 gives an overview of Internet users in Estonia in November 2005. A total of 66% of the respondents were Internet users at the time of the survey. There were more Internet users among men (71%) than among women (62%). Also, there were significantly more Internet users among younger people.

** Difference between the groups is statistically significant at p<0.01.

Table 1 also makes it possible to compare how different gender and age groups were distributed between Internet user types. There were significantly more men among Versatile Internet users and Public and practical information users. Women prevailed among Pragmatic work and information users and Entertainment and family information users.

Teenage respondents (15 to 19 year olds) were mostly Communication and entertainment oriented users. Young people aged 20 to 29 were also very active Internet users, being mostly distributed between Versatile Internet users, Communication and entertainment oriented users, and Pragmatic work and information oriented users. Among 30 to 44-year-olds, orientation to work and information related activities was most clearly visible. The two older groups were mainly distributed between more pragmatic and passive user types.

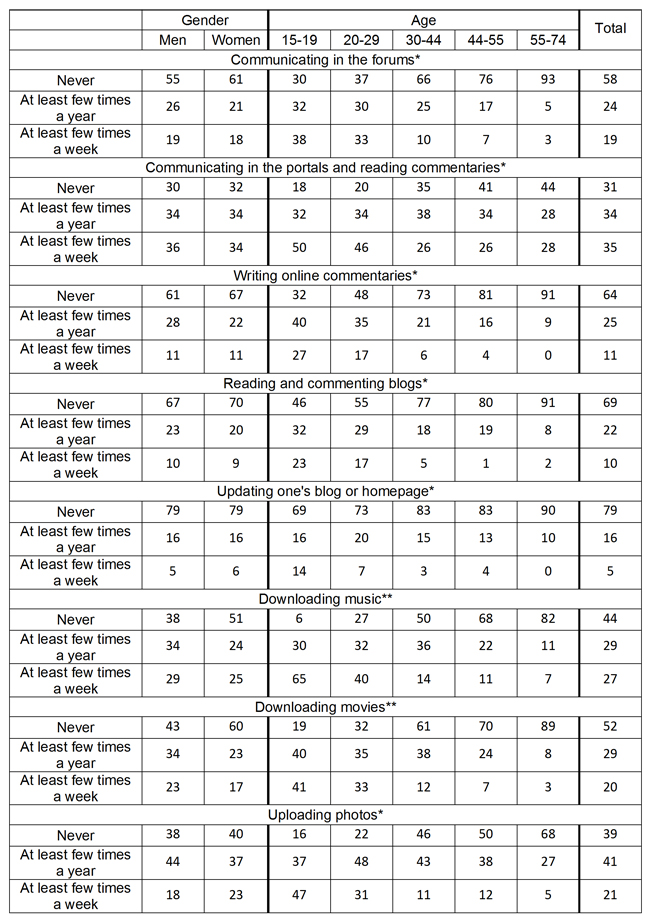

Table 2 gives an overview of the frequency of practices of online content consumption and creation among all Internet users (N=975), as well as by gender and age groups. The most common practice overall was communicating in portals and reading commentaries: a total of 69% of Internet users were engaged in that activity every now and then, whereas 36% of users had at least tried writing online commentaries. Thus, about half of the readers of commentaries were also engaged in writing them.

** Marks the indicators where difference between the groups is statistically significant at p<0.01 in case of both gender and age.

* Marks the indicators where difference between the groups is statistically significant at p<0.01 only in case of age.

The most popular content creation practice was uploading photos (62% of Internet users had done it at least a few times a year). Consumption of audio-visual content was also widespread: 56% and 49% of Internet users had downloaded music and movies, respectively. These activities were followed by communicating in forums (43% of Internet users).

The least popular practices were reading and commenting on blogs (32%) and updating one’s blog or homepage (21%).

Though men tended to engage more actively in those activities (except for updating one’s blog or homepage), in most cases the differences were not statistically significant. Downloading music and movies were the only activities that were significantly more practiced by men than by women.

Younger respondents were much more frequently engaged in most of the practices of online content consumption and creation; moreover, 15- to 19-year-olds were most active in all of the listed activities. Downloading music was most familiar to the youngest age group: only 6% of the teenagers had never done this. Other highly popular activities among the young were uploading photos, communicating in portals and downloading movies. Practices of online content creation were also more common among the youngest age group: 47% of the teenagers uploaded photos, 27% wrote online commentaries and 14% updated their blog or homepage at least a few times a week.

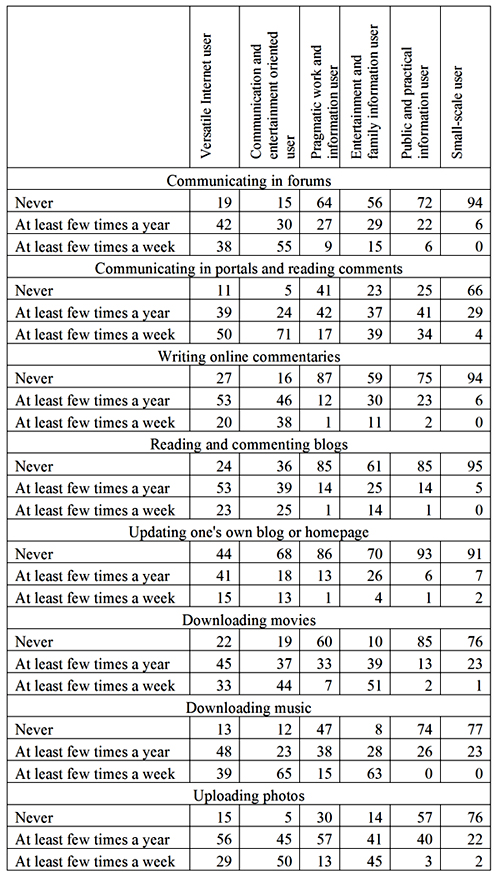

Table 3 compares practices of online content consumption and creation among Internet user types. It is important to note that the same activities formed a part of the input variables for the factor analysis and the subsequent cluster analysis, which provided the user typology. Most of these activities were a part of either the Entertainment factor or the Communication factor, which were more predominant among Communication and entertainment oriented users, and Entertainment and family information users.

The most active Internet users (the Versatile Internet user type) were also relatively active in content creation and consumption: for instance, the most active blog writers and readers belonged to this type. Among three user types – Pragmatic work and information users, Public and practical information users, and Small-scale users – only a few had tried the listed activities and even fewer were frequent users.

Entertainment and family information users, being fairly passive in regard to several listed activities, were relatively active in consuming certain type of online content (downloading music and movies) and in uploading photos.

Discussion

Our results showed that creating and consuming online content varied greatly between age groups and types of Internet users. For instance, online activities of the most active user type (Versatile users) also included active content creation. A large group of otherwise active Internet users (Pragmatic work and information users, and Public and practical information users) did not create or consume user-created content (that is, reading and commenting on blogs, communicating in forums etc.) very actively. This means that content creation skills are not directly connected to more pragmatic uses of the Internet. These patterns allow us to conclude that this kind of user typology makes it possible to estimate the diffusion of various skills and content-creation practices in the population.

Gender differentiated content-related online practices only in the case of downloading music and movies: men tended to be engaged more frequently in these two entertainment-related activities. This is in line with the findings by Kalmus (2006): although women use the Internet somewhat less frequently than men, they tend to use it more pragmatically and in a socially relevant way, for instance, to participate in the public sphere. We have to keep in mind, however, that significant differences still existed in the overall share of Internet users among men and women, as well as in the distribution of men and women between Internet user types.

Differentiation between Internet users and non-users was most notable on the age scale. Moreover, the youngest age group (15- to 19-year-olds) was most active in all of the practices of online content consumption and creation measured in this survey. Thus, in technical terms, we can speak of this age group as “Generation C” (cf. Bruns 2005). Besides particular age groups, this concept also refers to active and knowledgeable “information citizens”. Young Internet users in Estonia, however, tended to be predominantly passive content consumers, frequently downloading music and movies. They were, though, more active in participating in portals (almost half of 15- to 19-year-olds communicated or read commentaries in portals on a weekly basis, which was almost as frequent as uploading photos). In general, orientation towards audio-visual content (uploading photos and downloading movies and music) was strong among this age group, stressing the importance of multi-modal digital literacies. More sophisticated activities in terms of digital literacy (for instance, updating one’s blog or homepage) were also more common among the youngest group; however, these practices and the related skills were not widespread.

It should be pointed out, though, that this survey data does not make it possible to confirm whether such conclusions are fully applicable with regard to the practices of consuming and creating visual and audio-visual content, as the questionnaire included only the indicators of downloading movies and music and uploading photos. Therefore, this data is slightly biased towards consuming and creating verbal content, that is, more traditional reading and writing practices.

The notion of produsage, which covers closely connected practices of producing and consuming online content, can be applied to two pairs of activities in this survey: reading and writing online commentaries and reading and writing blogs. Our analysis showed that, in both cases, producing new content was a far more marginalized activity than consuming online content. Although writing online commentaries has a relatively long history in Estonia (online newspapers and portals have had open commentary spaces since the late 1990s), the potential of having everyone’s voice heard has not been fulfilled: the opportunity is still only used by a few active users, who become the “voice of the people”.

The results presented in this study raise questions regarding contemporary schooling and other socialisation processes, which should provide people with a multiple array of digital skills. More widespread content creation and consumption practices were mostly related to the private sphere, being largely entertainment-oriented (for instance, Entertainment and family information users were very active in downloading movies and music). Different user groups can meet each other mostly in educational and family spheres. However, previous research (MEDIAPPRO 2006; Kalmus 2007b) has indicated that young people do not talk about their Internet use with representatives of other generations: generally they do not ask advice from their parents or teachers or talk about their online experiences with them. Thus, we are facing a situation where traditional forms and patterns of education and socialisation are not fulfilling the function of obtaining digital literacies. It is debatable whether produsage environments are beginning to replace formal training and education (cf. Bruns 2006). To some extent, produsage is becoming a form of education in itself, in which peer-based advice becomes available to other participants in large-scale cooperative communities. It is, however, unclear to what extent it offers a critical perspective on one’s own and other people’s activities beyond these particular practices.

The data presented in this study made it possible to address some aspects of digital literacies. Firstly, it allowed us to see the diffusion of various practices and skills in the population. Secondly, it referred to predominant forms of knowledge representation users are creating through content production and consumption. This data, though, does not provide answers about the third layer of literacy – that of institutional management of power, which obtaining skills and putting them into practice is supposed to give to the digitally literate. It is difficult to discuss the nature or uses of digital literacy in this sense. Therefore, it is crucial to gain more understanding about how produsage, as one of the aspects of digital literacies, acts as a tool for the diffusion of interpretative skills and possibilities and as a tool for power management for those involved. The current pattern of content creation practices does not encourage discussion of the manifold multimedia literacies characteristic of Generation C that develop critical skills for successfully interacting in the wider social environment. Rather, this pattern refers to online media as a means of practicing one’s creativity, as a tool for self-expression and as an environment of a rather limited array of cultural consumption.

Also, it remains unclear whether this kind of content creation and consumption experiences can be transferred to other dimensions of society. In some cases self-regulatory, hobby-based online communities can be seen as an arena for constructing cultural participation and, through this, facilitating wider social participation (Runnel 2002). Still, the questions remain as to whether and how wide-scale entertainment and consumption-oriented practices of produsage are linked to social and political participation. For example, does participation in a content-creation based social network or in a large-scale produsage environment centred on uploading one’s photos increase or facilitate participation in other kinds of social movements or help one to practice one’s rights as a citizen? Can rules of self-regulation or ways of evaluating each other’s contributions in visual, textual or other forms, developing in an online produsage community, or commenting on and reading each other’s comments in a portal be linked with the understanding of the functioning of a civil society? Can the power mechanisms acting in produsage communities also be transformed into power and participation on a wider social scale?

Online communication environments in which the majority of the practices of online content creation and consumption take place are semi-private environments, being open to all users, but are mostly used for activities related to private life and relationships. Estonian Internet users are less involved in the domain of state-citizen communication, being more active only in reading and writing commentaries regarding topical news events. Usually the latter activities lack direct political influence. We suppose that a considerable number of Internet users would also practice content creation outside the entertainment and private sphere if there were meaningful opportunities available. The existing content creation opportunities in the actual political sphere, however, are mostly examples of token, not real, participation (Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt 2007). This situation, in fact, does not justify Estonian e-state related hype, which is used to support the claims of success in e-governance, e-education and related areas.

The study showed that at least three different questions, having both theoretical and practical aspects, have to be addressed in further research. The first set of questions involves practices of audiovisual content creation, not sufficiently represented in this survey. Along with the emergence of web environments focussed on creating, consuming and sharing visual and audiovisual content, further research should be carried out to gain more knowledge of the audiovisual aspects of multi-modal literacies. Secondly, as produsage is becoming a part of education, further studies should address the educational aspects of digital content creation and consumption, including looking at how they might change and are already changing existing patterns of education and socialisation. The third set of questions is connected with content creation as a form of power management on a wider social scale, including analysing whether cultural participation and content creation facilitate empowerment and democratic social and political participation.

Acknowledgement

The preparation of this article was supported by the research grants No. 5799, No. 6968 and No. 7162 financed by the Estonian Science Foundation. The data were gathered with the support of the target financed project “Estonia as an Emerging Information and Consumer Society: Social Sustainability and Quality of Life” (SF0180017s07).

References

Beljajev, K. (2006). Koolinoored autorina internetikeskkonnas (Schoolchildren as Authors on the Internet). Unpublished Bachelor thesis. University of Tartu, Department of Journalism and Communication.

Blanke, J. (2006). The Lisbon Review 2006: Measuring Europe’s Progress in Reform. Cologny/Geneva: World Economic Forum. Retrieved November 15, 2007, from: http://www.weforum.org/pdf/gcr/lisbonreview/report2006.pdf

Bruns, A. (2005). Gatewatching: Collaborative online news production. New York: Peter Lang.

Bruns, A. (2006). Towards produsage: Futures for user-led content production. In Sudweeks, F., Hrachovec, H., Ess, C. (Eds), Cultural attitudes towards technology and communication 2006 (pp 275–284). Murdoch: Murdoch University.

Economist Intelligence Unit (2006). The 2006 e-readiness rankings. A white paper. Retrieved January 18, 2007, from : http://a330.g.akamai.net

Kalmus, V. (2006). Will all grandmothers surf the Net? Changing patterns of digital gender inequality in Estonia. In Sudweeks, F., Hrachovec, H., Ess, C. (Eds), Cultural attitudes towards technology and communication 2006 (pp 505–520). Murdoch: Murdoch University.

Kalmus, V. (2007a). Socialization in the changing information environment: Implications for media literacy. In Macedo, D., Steinberg, S. R. (Eds), Media literacy: A reader (pp 157-165). New York: Peter Lang.

Kalmus, V. (2007b). Estonian adolescents’ expertise in the Internet in comparative perspective. Cyberpsychology: Journal of psychosocial research on cyberspace 1(1). Retrieved from : http://www.cyberpsychology.eu/view.php?cisloclanku=2007070702

Kalvet, T. (2007). The Estonian information society developments since the 1990s. PRAXIS Working Paper 29/2007. Retrieved February 4, 2008, from : http://www.praxis.ee/data/PRAXIS_WP_29_NETIS_Kalvet.pdf

Kellner, D., & Share, J. (2007). Critical media literacy, democracy, and the reconstruction of education. In Macedo, D., Steinberg, S. R. (Eds), Media literacy: A reader (pp 3-23). New York: Peter Lang.

Kress, G. (2003). Literacy in the new media age. London & New York: Routledge.

Livingstone, S. (2004). Media literacy and the challenge of new information and communication technologies (online). London: LSE Research Online. Retrieved December 28, 2007, from http://www.eprints.lse.ac.uk/1017

MEDIAPPRO (2006). A European research project: The appropriation of new media by youth. Brussels: Chaptal Communication with the Support of the European Commission / Safer Internet Action Plan. Retrieved January 30, 2008, from http://www.mediappro.org/publications/finalreport.pdf

Nørgaard, O. (2000). Economic Institutions and Democratic Reforms. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Panagiotou, A. (2001). Estonia’s Success: Prescription or Legacy? Communist and Post-Communist Studies 34(2), 261-277.

Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt, P. (2006). Information technology users and uses within the different layers of the information environment in Estonia. Dissertationes de mediis et communicationibus Universitas Tartuensis, 4. Tartu: Tartu University Press. Retrieved February 4, 2008, from http://hdl.handle.net/10062/173

Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt, P. (2007). Participating in a representative democracy: Three case studies of Estonian participatory online initiatives. In Carpentier, N., Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt, P., Nordenstreng, K., Hartmann, M., Vihalemm, P., Cammaerts, B., Nieminen, H. (Eds). Media technologies for democracy in an enlarged Europe: The Intellectual work of the 2007 European Media and Communication Doctoral Summer School (pp. 171-185). Tartu: Tartu University Press. Retrieved January 30, 2008, from http://www.researchingcommunication.eu/reco_book3.pdf

Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt, P., & Kalvet, T. (2008, forthcoming). Infokihistumine: Interneti mittekasutajad, vähekasutajad ning hiljuti kasutama hakanud (Information stratification: Internet non-users, small-scale users and recent adopters). Working Paper. Tallinn: Praxis.

Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt, P., Vihalemm, P., & Viia, A. (2007). Digital opportunities as a development factor. In Heidmets, M. (Ed). Estonian human development report 2006 (pp 95-105). Tallinn: Public Understanding Foundation.

Runnel, P. (2002). Anthropology, media and communication studies: Beyond texts. Nord Nytt 85, 53-67.

Subrahmanyam, K. (2007). Adolescent online communication: Old issues, new intensities. Cyberpsychology: Journal of psychosocial research on cyberspace 1(1). Retrieved from http://www.cyberpsychology.eu/view.php?cisloclanku=20070707021

World Economic Forum (2007). Global Competitiveness Report 2007-2008. Retrieved January 30, 2008, fromhttp://www.gcr.weforum.org/