Information Society from a Comparative Perspective: Digital Divide and Social Effects of the Internet

Anna Galácz1, David Smahel22Institute for Research of Children, Youth and Family, Faculty of Social Studies,

Masaryk University, Brno Czech Republic

Abstract

Introduction

In our article, we show some basic results from the World Internet Project, an international research focused on examining the influence of computers, the Internet and related technologies on the individual, family and society (see chapter "About the World Internet Project"). The presented article is mainly a report from the project which gives us a frame for other pieces of research from the international perspective. Although the paper is mainly a report, we also try to show some basic concepts of other authors which are connected with presented results. The main goal of this paper is to give readers a general view on Internet use in four studied countries and give them a basic image about the effects of the Internet on time spent with families and the overall contact with families and friends.

The phenomenon and the development of the digital divide is one of the most investigated research topics on the field of new media and ICT research. According to the simplest definition the concept of digital divide describes the phenomenon that there is a difference between certain social groups in the likelihood of accessing and using the Internet. Theories usually make a distinction between different kinds of divides: the most general is to separate the so-called global digital divide and the social digital divide. While the first one refers to the differences between countries and greater geographic regions, the latter refers to inequalities between different social groups in a given social system (e.g.: in countries, smaller regions or groups) (Norris, 2001).

On the field of social digital divide, researches often focus on the social demographic features along which these differences develop. According to the analyses, these determining factors are more or less the same in most countries, of course with different tones. These are usually income, education, age and gender, while in some cases geographic location and race are also important. (Bognár-Galácz, 2004)

Researches also try to find out what will happen with these inequalities in the future. The optimists developed the so-called normalization thesis which suggests that as the diffusion of Internet usage goes along, these inequalities will decrease to completely disappear after a while (see for example Rose 2004). On the contrary, the supporters of the stratification thesis assume that the inequalities will remain, although somehow transformed, and the most decisive factor will be how certain groups use the Internet and how good their usage skills are. (DiMaggio-Hargittai, 2001)

Recently several analyses tried to find answers to the aforementioned questions, but the picture is still far from clear: some results have supported the normalization theory, while others the stratification theory. (Dutton et al., 2006)

Now we will present basic concepts of the social effects of Internet use. Although a lot of research has been done, the situation is similar to the digital divide issue: research results are sometimes in contradiction and the situation is changing on an almost day-by-day basis.

Tyler (2005) reviewed several studies about the social effects of the Internet and suggested that the Internet may have less impact on human social life that it is frequently supposed. He concluded that "the Internet seems to have created new ways of doing old things, rather than being a technology that changes the manner in which people live their lives". The Internet does not often create new forms of behavior but it gives new tools to current forms of behavior.

Krauts' first study (1998) stated that respondents in his study (208 new Internet users) were after 2-3 years of the Internet use less socially involved and more lonely and depressed. This study were reexamined and criticized by many authors and alone Kraut his team conducted an ongoing study (Kraut et al., 2002) where they found no negative effects of the Internet on individuals. They suggested that the Internet had a small but positive effect on social involvement and psychological well-being. Authors presented more positive effects than in previous work.

One of the studies which tried to confirm Krauts' research was made in Sweden (Wastlund et al, 2001), where authors surveyed 500 students of at Karlstad University aged from 18 to 61 years old. Contradict to first Kraut's study they did not find the relationship between Internet use and psychological well-being.

Another research on 984 students (Weiser, 2001) confirmed very low effects of Internet use on the psychological well-being, but stated an interesting hypothesis about the connection between the manner of Internet use and effects on the measure of social integration. The author revealed two basic ways of Internet use, first for social and interpersonal usage (so called SAR) and for informational and professional purpose (GIA). Weiser's research results show that the Internet use for informational purposes was associated with increased social integration and the use for social and interpersonal usage was on the other hand connected with decreased social integration.

In this paper, we will investigate the digital divide in four countries in the case of three important socio-economic variables: gender, age, and education. Since our data is not longitudinal, we only can give a snapshot about the situation of digital divide in the investigated countries. But, since these four countries are on different stages of penetration we can make some conclusions about the possible important factors that determine digital divide.

The second part of our paper is concentrated on the problem of social effects of the Internet on individuals and family. We mainly analyzed the perceived changes in spending face to face time with families after people started using the Internet and also the effect of Internet use on overall contact with family and friends.

Country profiles

To give the reader a basic overview about the countries in the form of a presented comparison, we show a table of country profiles, see Table 1:

| United States | Czech Republic | Hungary | Republic of Singapore | |

| Land Area | 9,161,923 sq km | 77,276 sq km | 92,341 sq km | 683 sq km |

| Population | 300,000,000 | 10,235,455 | 9,981,334 | 4,492,150 |

| Density per sq km | 32 | 132 | 108 | 6577 |

| Grow rate | 0.9% | -0.1% | -0.3% | 1.4% |

| Ethnicity/race | White 75.1%, Black 12.3%, Asian 3.6%, Hispanic 12.5%, other 6.5% | Czech 90.4%, Moravian 3.7%, Slovak 1.9%, other 4% | Hungarian 92.3%, Roma 1.9%, other or unknown 5.8% | Chinese 76.8%, Malay 13.9%, Indian 7.9%, other 1.4% |

| GDP per capita | $42,000 | $18,100 | $16,100 | $29,900 |

We can see that there are big differences between the selected countries, USA is the biggest country with very heterogenous population and highest GDP, Singapore is the smallest country (because it is actually a city), which is pretty rich compared to post-communist countries such as Hungary and the Czech Republic. Hungary and the Czech Republic are the most similar countries in our comparison, with similar land area, population and GDP, so it will be interesting to see if these similarities will also remain in the characteristics of Internet penetration and the social effects of the Internet.

About the World Internet Project

The World Internet Project was initiated by UCLA in California and NTU School of Communication Studies Singapore in the summer of 1999. Since then more than 15 countries have joined the project form four continents. The WIP research has several characteristics that make it special among the fortunately increasing number of surveys investigating the social effects of the Internet.

Compared to recent surveys focusing on users one of the important novelties of WIP is the extension of the investigation to non-users as well. This allows the investigation of both the transitions between the groups of users and non-users and the dynamics of changes and the wide comparison among opinions and attitudes of both groups. By these means the reasons of "keeping away" can also be cleared.

WIP tries to create a map of the overall social effects of the Internet, not merely from one point of view. This is why we have elaborated the project of a longitudinal ten-year research period the investigations of which are repeated each year. This gives a possibility to constantly follow up the kind of short and long term effects Internet use has on people's opinions, habits and the lives of households. WIP analyses also can be useful for business and government policies for creating sufficiently elastic strategies targeting the most relevant questions and issues by following up changes.

This is a survey of international comparison. It helps us to get to know the social changes connected with the Web in different countries and regions. The questions of the questionnaires of each nation include variables measuring general "social disposition", opinions on electronic technologies and the Internet and trust in different institutions as well. This makes comparison possible in these fields. According to their individual interests, researchers of each country may add special, particular questions and subjects relevant to their given country. Research-groups that take part in World Internet Project inform each other about achieved results and discuss their experiences and conclusions in regular annual conferences.

The possibility of comparison is provided by the so called common question set. These common questions are included to every national survey and produce approximately 70 common variables. In 2006, the common variables were integrated for the first time into one common database which allows for more sophisticated research.

Methodology: Data samples

The data analyzed in this paper was collected and is owned by the following institutes:

(1) Czech Republic: Institute of Children, Youth and Family Research, Faculty of Social Studies, Masaryk University, Brno

(2) Hungary: Fieldwork was conducted by TÁRKI, Social Research Center, procurer and owner is ITHAKA Kht.

(3) Singapore: Singapore Internet Research Centre (SiRC), Nanyang Technological University

(4) USA: USC Annenberg Center for the Digital Future, Los Angeles

We present data on population samples of 18 years of age and older, all four samples were made representative for each country. The following table shows more information about each of the presented data samples:

| Country | Number of respondents | Data collection | Method | Representativity |

| Czech Republic | 1706 | September 2006 | Face to face interviews | Representative for: sex, education, age, region, and the size of the respondent's domicile |

| Hungary | 3970 | May 2006 | Face to face interviews | Representative for Hungarian population aged 14 years old and older and for Hungarian households |

| Singapore | 1000 | 2006 | Telephone interviews | Representative for Singaporian population of age 18 and older |

| USA | 2269 | 2006 | Telephone interviews | Representative for US population of age 12 and older |

These four data sets were added into one SPSS database and were analyzed according to the goals of our presentation.

Results

Penetration and digital divide in 2006

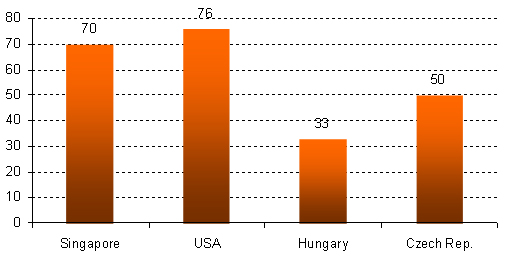

General penetration numbers are very different in the four countries. Two of them - USA and Singapore can be characterized with very high percentages: 76 and 70 percent of the adult population are a regular Internet users. The rate of users in the Czech Republic can be considered moderate (50%), what is in the middle range of the EU countries. The rate of users in Hungary is very low (33%) compared to either of these countries as well as to other European nations, see Figure 1.

Here we do not aim for understanding these differences in details: we can assume that a complicated relationship of historical, economical, attitudinal and cultural factors lies behind the different numbers. But the fact that we can compare four countries with different penetration numbers allows us to investigate the situation of different divides and perhaps we can see some fragments of their development.

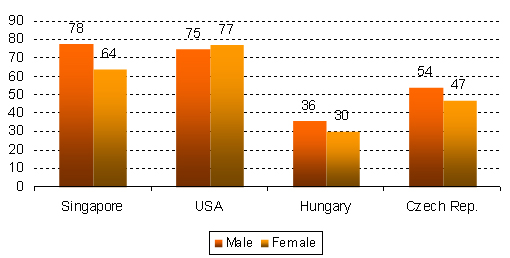

The first variable we investigate in this context is gender. In most countries the gender differences are usually smaller than other gaps. In the case of the US, the difference in the rate of users among men and women is almost irrelevant, only 2% (with a prevalence of women). The differences observed in Hungary and in the Czech Republic are somewhat greater, but still quite small - 6 and 7%. However this gender gap is much wider in Singapore (14%) although the overall penetration rate is very high, see Figure 2. This could be caused by the fact that the traditional role of women is stronger in Singapore than in other countries.

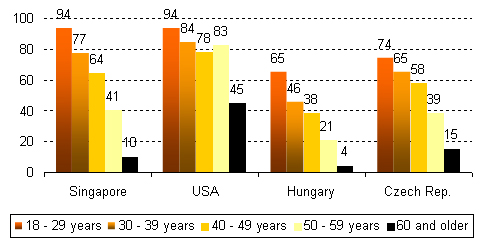

Concerning age, we can conclude that people of younger age tend to use the Internet more often. The members of the oldest age group, those who are 60 years old or older, are especially lagged behind - this holds in every examined country. This is a general pattern, however the differences vary from country to country. The differences are the smallest in the US, in this case the relationship is not even linear, and the rate of users is relatively high even in the oldest cohort. The differences are bigger in the other three countries. It is worth mentioning that despite the very different general penetration numbers the gap in Singapore is almost as big as in the two East-European countries. Moreover, in relative terms, the lag of the oldest age groups is greater in Singapore, see Figure 3.

The same conclusions can be drawn when investigating the role of educational level. The importance of education is obvious: quite serious differences have developed in all the four countries from this respect. Again, in the US the gaps are smaller. In Hungary the role of education is traditionally very important, and the situation seems to be the same in Singapore. In the Czech Republic, differences are smaller, but the effect of education is unquestionably relevant.

What are the main conclusions from the aforementioned numbers? The most important thing we can state is that the relationship between the level of penetration and the state of digital divide is not obvious. Even in countries with high penetration numbers, serious inequalities in some respect can be observed, while countries with low penetration can have narrower gaps.

This probably means that the neither of the two concepts concerning the future of digital divides is inclusive: penetration is not the only factor shaping this development. Cultural factors and national characteristics have a serious impact on how the different divides develop over time.

The importance of cultural effects can also be illustrated in the next figure. As one can see in Figure 5, the main reasons for not using the Internet are very different in the four countries, irrespective to the penetration level. The US and the Czech Republic are somewhat similar: in these countries the most important reason of not using the Internet is the lack of a proper tool: a computer or Internet access. In Hungary the most important reason is motivational: a lot of non users think that the Internet is not useful or interesting enough. However, in the case of Singapore the most important obstacle is cognitive: a majority of non users simply does not know how to use the Internet. Of course, we can see an obvious relationship too: in economically poorer countries (Hungary, Czech Republic) pure financial reasons (‚too expensive') have more relevance, but the overall differences should call our attention to the important role of cultural factors.

Social effects of Internet use

In this chapter, our goal is to show how the Internet influences the amount of time spent face to face with family members and what are the changes in the measure of overall contact with family and friends.

The respondents of the World Internet project were asked to answer the following question:

"Since being connected to the Internet at home, the members of your household have spent more face-to-face time together, spent less face to face time together, or spent about the same amount of face to face time together?"

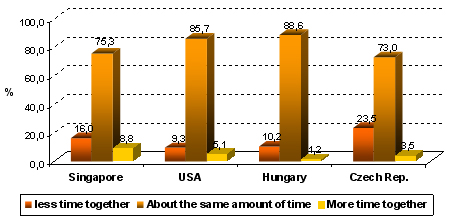

The Figure 6 shows the frequencies of respondents' answers to this question:

In general, most of the respondents in every country stated that they spend "about the same amount of time" with their families face to face (73 - 89%), although the higher ratio of respondents think that they spent less time with family; overall for four countries it is 13.8% (less time with family) against 5.1% (more time). The overall differences between countries are significant ?2(6, N = 3791) = 163.2, p = .000. The highest portion of respondents (23.5%) claiming they spend less time with family since they connected to the Internet at home is in the Czech Republic. Country differences are interesting because they do not copy any characteristic of Internet use at all. All we can see is a similarity with the overall time spent with families, which is highest in Singapore (in average 34 hours socializing with family per week), somewhat lower in Czech (27.5 hours per week) and much lower in Hungary (only 8.3 hours per week); there was no question regarding the total time with family in the US' questionnaire. On the other hand, a much lower percent of respondents in Hungary stated that they spent less time with families than in Singapore and Czech. We can hypothesize that high amount of time spent with family can be decreased by Internet use, but the Internet has lower effects on families where the amount of socializing is already lower.

This hypothesis can be partly supported by the analysis because we found no significant differences in any country in the amount of time spent with family between those who stated they spend "less time with family" and the "same time with family". Both groups socialize with their families in a similar rate now, so if some people really spend less time with their families now, they had to spend more time with them before. But it could also be that it is just a normal phrase to say "the Internet is eating time that I would spend with my family" and the Internet has in real no effect.

The differences in answers to this question were not significant according to the gender of respondent in any country except US, where 13% of men said they spend less time with their family opposed to 7% of women answering the same.

We also tried to examine the presented data in the opposite way; we asked how much time people who say they spend "less time with family" and "about the same time" actually spend on the internet. Table 3 shows the results, the average for "more time with family" was not calculated because there were not enough respondents in the category.

| "Less time with family": average hours weekly on the Internet (N) | "About the same amount of time": average hours weekly on the Internet (N) | Significance of difference between the two previous columns F (p) | |

| Singapore | 19.5 hours (105) | 15 hours (272) | 5.2 ( p = 0.022) |

| USA | 13,1 hours (151) | 10,2 hours (1293) | 8.1 (p = 0.04) |

| Hungary | 7,2 hours (74) | 8 hours (679) | 0.38 (p = 0.539) |

| Czech | 8,5 hours (179) | 6,9 hours (711) | 4.1 (p = 0.44) |

We can see that the difference in time spent weekly on the Internet was significant except for Hungary: people who say that they spend less time with family since they started using the Internet tend to spent more hours on the Internet on average weekly. The difference is 4.5 hours in Singapore, 2.9 hours in USA and 1.6 hours in Czech. We can speculate if people truly took this time (the difference between first and second group in table) from time spent with family or if they just have a higher tendency to reflect the fact that they spend a lot of time on the Internet onto their lack of time spent with family. Both these possibilities should be verified by future research.

We also tried to find another variable which could explain the differences between people who spend "less time with family" and the "same amount of time with family" and also between countries, but the search was not quite successful. The best explanation of the differences was provided via answers to the following question:

"Satisfaction with the way family discusses items of common interest and shares problem solving according to face to face time in family together."

With possible answers: "Almost always", "Sometimes", "Hardly ever".

Figure 7 shows answers to this question according to the change of the time spent with family since using the Internet. The answer "Hardly ever" was very rare and was not possible to add it in the analysis.

We can see differences in every country between respondents who said they are "almost always" satisfied with the way family discusses items of common interest and shares problem solving and between those who said they are "sometimes" satisfied: there is a tendency that less satisfied people with family discussions spend less time with their families since they starting using the Internet at home. The differences are significant on the 0.05 level except for Singapore (Hungary: ? = 18.8, p = 0.00; USA: ? = 12.4, p = 0.02; Singapore: ? = 4.9, p = 0.085; Czech did not have this question in their questionnaire). We can have a hypothesis that people who are less satisfied with their family life tend to spend less time with their families because of Internet use, since on the Internet they can socialize with other people.

Now we will focus on the level of overall contact with families and friends as an effect of Internet use. Respondents answered the following question:

"Has the use of Internet increased or decreased your contact with the following groups?"

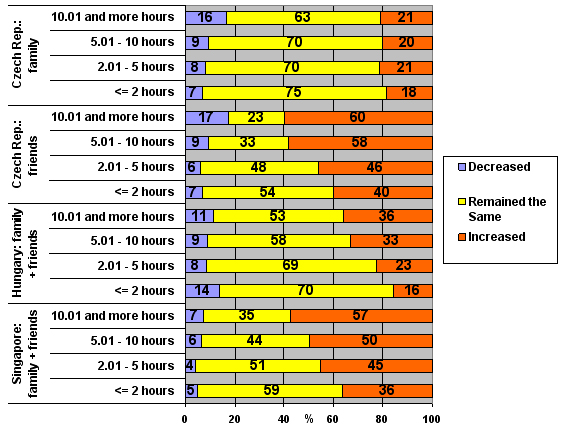

Questionnaires in Singapore and Hungary both used the category: "family and friends", while the Czech study separated these two groups, USA did not include such a question in their questionnaire. Figure 8 shows basic frequencies of answers to this question.

Most respondents answered that their contact "remained the same" (43-71%), but in every country a higher portion of respondents said that their contact increased rather than decreased. In the Czech Republic, a total of 46% respondents stated that the Internet increased their contact with friends (8% decreased) and 21% stated it increased their contact with family (9% decreased). In Singapore, a total of 50% agreed that the Internet increased their contact with "family and friends" (7% decreased), in Hungary we can see a largest balance between people stating that the Internet decreased or increased their contact with friends and family, a total of 21% think their contact was increased and 12% that it was decreased.

If we think about these answers in the context of previous graphs, it becomes clear that respondents included online contacts with their friends and families, since otherwise the results would be similar to those in previous question. As opposed to the previous part, a higher portion of respondents think that their contact was increased in total, meaning that people probably often use the Internet for communication with friends and families. A direct comparison with the previous question is possible only in the Czech Republic where respondents were asked directly about contact with family and a total of 21% stated their contact was increased although in the previously analyzed question only 3.5% agreed that they spent more face to face time together. So it's clear that about 20% people contact their family members more often than before by e-mails, online messengers and perhaps other technologies (Skype etc.). Right now, we can only speculate about the frequency and quality of this online contact with family members increasing the frequency of communication from the respondents' point of view.

We also looked at gender differences in overall contact with family and friends and no significant results were found in any country.

Then we tried to find a variable which correlated the most with these changes in overall contact with family and friends and revealed that the highest correlation is paradoxical with hours spent on the Internet at home. This result is shown in Figure 9.

Results in any country (both in Czech) were significant on the level p < 0.05. We can first look at results in Singapore and Hungary, where respondents answered together for "family and friends". We can see a similarity pattern: respondents who spent more hours on the Internet stated more frequently that the Internet increased their contact with "family and friends". In Hungary, 36% of people who spent more than 10 hours weekly on the Internet at home think that the Internet increased their contact as opposed to 16% of those who spent less than 2 hours weekly. In Singapore, 57% of respondents spending over 10 hours on the Internet and 36% of those spending less than 2 hours on the Internet agreed with spending more time with family and friends. There is also a similar pattern in the Czech Republic, but only for friends: 60% of people who spend 10 and more hours on the Internet weekly think that their contact was increased as opposed to 40% of people who spend less than 2 hours. An interesting thing to note is that there is no such pattern for contact with families in Czech: between 18 - 21% of people in our categories think that their contact was increased but it is not significantly different when compared to time spent on the Internet (it does not become significant if we exclude decreased time with families). What is the biggest difference in contact with families in Czech? It is the 16% of them in the category more then 10 hours weekly on the Internet, who say, that their contact with family was decreasing: that means that "heavy users" spend less time with their families.

We can hypothesize based on presented results that the Internet mostly increases contact with friends (looking at differences between answers for family and friends in Czech) and that the contact increases more with more time spent on the Internet at home: people probably spend more time e-mailing and/or using instant messengers talking with friends. The influence on family is not clear yet, but we can guess from results in Czech that the amount of time spent on the Internet has no influence on increasing contact with family, although it could be that Internet "heavy users" decrease overall contact with their families, corresponding with results in previous parts of this article.

Discussion and Conclusions

The main conclusion of the digital divide part of our paper is that there is no fixed path of development of the digital divide. It means that greater penetration does not automatically mean the diminution of these differences in every respect. Cultural factors and characteristics have a very important effect on shaping the development of digital divides. This also means that none of the concepts mentioned in the beginning of our paper can be universally valid. Both the thesis of normalization and stratification can be justified by results of analyses since these developments are different in different context. So, in the case of digital divide, the observations often made on Internet related social issues are also plausible: none of the extreme scenarios are taking place, but moderate types of development are happening (DiMaggio et. al, 2001).

In the field of research on digital divide, our results suggest that, both in national and international studies, it is always very important to take cultural factors into account. It could be especially useful to compare the diffusion of the Internet with other diffusion processes and find the cultural effects which shape the phenomenon of social diffusion. Deeper analysis of the factors hampering adaptation can help meet this goal.

Also, as literature suggests, besides the raw penetration numbers it is more and more important to investigate the so called second level divide (Hargittai, 2002), which is the difference in user skills and habits.

If we look retrospectively on presented results, we can see that most people stated that the Internet did not change the time spent face to face with families and the overall contact with families was not changed a lot. The Internet probably mediated higher contact with friends which is realized through the Internet while people are sitting at home. In this sense, we can agree with Tyler (2005) who suggested that the impact of the Internet on social life is probably lower than frequently assumed and that the Internet is first of all a new tool for doing "old things in new ways". Such as the Internet is a special tool for the communication with friends and family.

Tyler's hypothesis is also supported by our finding that there is some connection between the Internet's ability to lower face to face contact in those families where the respondents are less satisfied with the way family discusses items of common interest (see Figure 7). We can speculate that for some people the Internet could be an environment where they can escape their family problems and can communicate with other people from home.

We found inspiration in the results of Weiser (2001), who defined two manners of Internet behavior: using it for social and interpersonal purposes and using it for informational purposes. We can say in general that it is not easy to study the influence of Internet use, first of all it is clear that there is not just one way to use the Internet. The manners of Internet use are just as various as human beings and we should speak about the influence of specific environments and specific ways of Internet use and not about the global influence of the Internet. This is also an appeal for future research: to study specific Internet environments and to give answers regarding how these environments influence the life of people. Another appeal is to compare different countries and cultures: our results suggested that there are big and deep differences even between countries with very similar characteristics, such as Czech and Hungary. We must think about the base of these differences and deepen our analysis and understanding of specific phenomenon and cultural specifics. The global country comparison can give us a broader view like in this article but it is also important to study special subgroups and themes in different countries, such as "heavy users", specific discussion groups, people endangered by Internet addiction, impact on family relationships etc. If we read research results from one country, we can not rely on the fact that the findings will be the valid in other countries. The cultural influence on family is quite probably much bigger than Internet influence is (which is also a hypothesis for future research). The specific people environment is what creates Internet specific cultures, but the culture is also influenced retrospectively by the global culture by the Internet. So it is plausible to speculate about a kind of spiral and it is a task for researchers to reveal how this truly works.

We must also think about presented research limitations. We presented only very broad quantitative results on representative samples in four countries. Our results do not offer deep details, we simply presented global trends and a global view on the problematic. Presented results should simply be considered a frame for deeper research and analysis. We hope that the World Internet Project could also become an important source of data for such intercultural analysis.

References

[2] DiMaggio P., Hargittai E., (2001): From the 'Digital Divide' to 'Digital Inequality': Studying Internet Use As Penetration Increases", http://www.princeton.edu/~artspol/workpap/WP15%20-%20DiMaggio%2BHargittai.pdf

[3] DiMaggio P., at al (2001): The Social Implications of the Internet, Annual Review of Sociology, 27:303-336.

[4] Dutton, W. H., Shepherd, A., di Gennaro, C. (2006): Digitális megosztottságok és digitális döntések: Az internet terjedésének és használatának brit és nemzetközi mintázatai (Digital divides and digital choices), in: Dessewffy T. - Fábián Z. - Z. Karvalics L. (ed.): Internet.hu 3, TÁRKI, Budapest. (In Hungarian)

[5] Hargittai E., (2002): Second Level Digital Divide, First Monday, 7(4)

[6] Norris, P. (2001): Digital Divide? Civic Engagement, Information Poverty and the Internet in Democratic Societies, Cambridge University Press

[7] Tyler, R., T. (2002). Is The Internet Changing Social Life? It Seems the More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same. Journal of Social Issues. 58, 1, pp. 195 - 205

[8] Kraut, R. E., Patterson, M., Lundmark, V., Kiesler, S., Mukhopadhyay, T., & Scherlis, W. (1998). Internet paradox: A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological wellbeing? American Psychologist, 53, 1017-1032.

[9] Kraut, R., Kiesler, S., Boneva, B., Cummings, J., Helgeson, V., & Crawford, A. (2002). The Internet paradox revisited. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 1, 49-74

[10] Rose, R. (2004): Governance and the Internet. In Yusuf, S., Altaf, M.A., & Nabeshima, K. (eds.), Global change and East Asian policy initiatives. New York: World Bank Group

[11] Wastlund, B.A., E.; Norlander, T. & Archer, T. (2001). Internet Blues Revisited: Replication and Extension of an Internet Paradox Study. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 4, 3, pp. 385 - 391

Acknowledgements:

David Smahel acknowledges the support of the Czech Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (MSM0021622406 and 1P05ME751) and Faculty of Social Studies, Masaryk University.

In 2006 the Hungarian World Internet Project was funded by the National Office for Research and Technology. Anna Galacz also acknowledges the support of the Hungarian Scientific research Fund (T/F 043757).